As sustainable construction and operational techniques are becoming increasingly widespread, many homeowners, building owners and companies are seeking to incorporate sustainable building strategies into their projects and businesses. As a result, local and national guides addressing sustainable building practices have been developed.

The International Green Construction Code,® 2018 Edition, published by the International Code Council,® is a third edition and part of a family of comprehensive, coordinated and modern model codes, including the International Building Code,® International Residential Code® and International Energy Conservation Code,® along with 11 other I-Codes published by ICC.

If you perform work in a jurisdiction with a “green” code in effect, you should be aware of new requirements contained in the 2018 IgCC.

Green codes

The intent of green codes is to provide for the health, safety and life of the built environment; increase the economic and resource efficiency of buildings; reduce the effects of climate change through more resilient buildings, communities and cities; and provide for the best modern buildings without compromising future generations’ needs.

The IgCC provides a whole-systems approach to the design, construction and operation of buildings and includes cost-effective measures that result in reduced operating costs, better indoor environments, reduced effect on natural resources, and improved neighborhood connections and walkability.

As a public-private collaboration, IgCC provisions are coordinated with IECC, ASHRAE Standard 90.1, “Energy Standard for Buildings Except Low-Rise Residential Buildings,” and many other referenced standards, helping streamline code development and adoption. The intent of 2018 IgCC compliance is to reduce energy and environmental effects through high-performing building design and construction while conserving natural resources.

In 2015, ICC joined with ASHRAE, The American Institute of Architects, Illuminating Engineering Society and U.S. Green Building Council to co-sponsor ASHRAE Standard 189.1, “Standard for the Design of High-Performance Green Buildings Except Low-Rise Residential Buildings,” which reflected a Memorandum of Understanding signed in 2014 to better align green building goals through ASHRAE Standard 189.1, IgCC and the LEED® certification system. As part of the agreement, IgCC’s technical content is based on provisions in the 2017 edition of Standard 189.1 developed using the American National Standards Institute-approved ASHRAE consensus process.

Before the agreement, the 2012 and 2015 IgCC versions included Standard 189.1 as a project compliance option. Standard 189.1 and now the 2018 IgCC address site sustainability, water-use efficiency, energy-use efficiency, indoor environmental quality, materials and resources, and construction and plans for operation.

For example, the 2018 IgCC added new requirements for vegetative roof systems and construction waste. It also updated requirements to reflect changes in ANSI/ASHRAE/IES Standard 90.1-2016, including reference to climate zone 0; revised envelope requirements (with associated revisions to an informative Appendix E); conversion of Energy Performance Option A to a Performance Cost Index; and addition of a new informative appendix with an energy compliance path that builds on the IECC instead of Standard 90.1. The IgCC establishes baseline green requirements and allows for above code systems. It establishes minimum requirements for buildings, providing a natural complement for voluntary green rating systems that may extend beyond the IgCC’s customizable baseline. The IgCC provides language that establishes a baseline for new and existing buildings related to energy conservation, water efficiency, site effects, building waste, material resource efficiency and other sustainability measures.

To ensure enforceability, the IgCC was reviewed by the same experts who develop building codes and standards enforced by code officials daily. The IgCC creates a regulatory framework for new and existing buildings, advancing and complementing the green building momentum created by popular rating systems.

The idea of green building is it does not result in any significant increase in an average life-cycle cost as a result of the availability of materials and savings stemming from reduced operating costs, lower energy usage and higher property values. Studies conducted by environmentalist Gregory Kats, SERA Architects Inc., Portland, Ore., X-energy, Rockville, Md., and Davis Langdon, a global construction consultant company based in London, have shown the cost for green construction is not much higher than traditional construction.

Using the IgCC

With the publication of the 2018 IgCC, USGBC predicts an increased interest from state and local jurisdictions for adopting the code. However, according to ICC’s website, www.iccsafe.org, only nine states and the District of Columbia have adopted the 2015 or earlier version of IgCC or a locally developed green code with no state yet to adopt the 2018 IgCC.

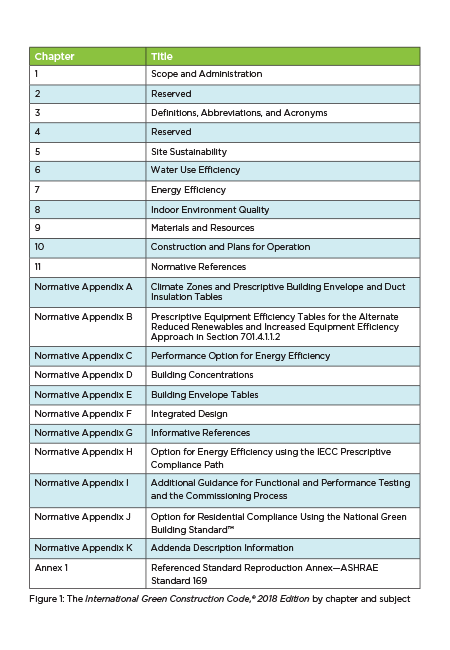

The IgCC is formatted using ICC’s code format and contains Chapters 1-11, Appendixes A-K and Annex 1 (see Figure 1). Appendices in the 2018 edition are treated differently from other I-Codes’ appendices, which are provided to offer optional criteria to the provisions in the main chapters of the specific I-Code. These appendices are identified in two categories: normative appendices (mandatory requirements) and informative appendices, which provide additional information but are not mandatory provisions and not part of the code.

The two appendices that relate to roof assemblies are Appendix A (mandatory), “Climate Zones and Prescriptive Building Envelope and Duct Insulation Tables,” and Appendix E (nonmandatory), “Building Envelope Tables,” which provides minimum R-values for nonresidential, residential and semiheated roof assemblies based on climate zone. The technical portion of IgCC has a number in parenthesis following the IgCC section number that corresponds to the section number in Standard 189.1.

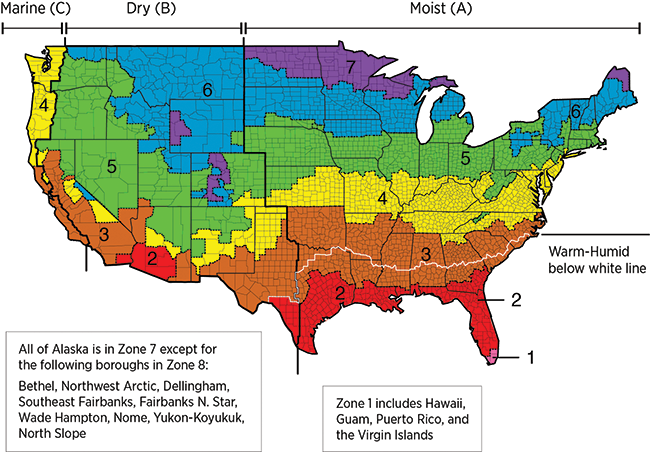

Chapter 5—Site Sustainability and Chapter 7—Energy Efficiency are two IgCC chapters that directly affect roof design and installation. Section 501.3.5.3 Roofs requires buildings and covered parking roof surfaces for building projects in climate zones 0 (not present in North America), 1, 2 and 3 (shown in Figure 2) to have a minimum of 75% of the roof surface covered with products that have a minimum three-year-aged solar reflectance index of 64 for roof systems with a slope less than or equal to 2:12 and a minimum three-year-aged SRI of 25 for roof systems with a slope of more than 2:12.

Figure 2: Climate zones. Source: U.S. Department of Energy

Areas to be excluded from the calculated required area include the area occupied by one or more of the following: roof penetrations and associated equipment; on-site renewable energy systems; portions of the roof used to capture heat for building energy technologies; roof decks and rooftop walkways; and IgCC-compliant vegetative terraces and roof systems. The required SRI is determined in accordance with ASTM E1980, “Standard Practice for Calculating Solar Reflectance Index of Horizontal and Low-Sloped Opaque Surfaces.”

The 2018 IgCC considers vegetative terraces and roof systems as containing plantings capable of surviving in the local microclimate, which includes but is not limited to precipitation, temperature and wind. Similarly, the growing medium in which the plants are to be placed also must support the plantings in the local microclimate. The installation of plantings also must meet the requirements of the roof covering manufacturer’s instructions and provide the intended coverage within two years of the issuance of the final certificate of occupancy. The use of potable or reclaimed water to irrigate plantings is prohibited after the plants are established or 18 months after the initial installation of the plants, whichever is less. After 18 months or when the vegetation is established, the irrigation system for potable or reclaimed water must be removed unless the authority having jurisdiction approves the continued use of on-site reclaimed water for vegetative roof system irrigation.

In a related section in Chapter 10—Construction and Plans for Operation, roof surface materials selected to comply with the requirements of Section 501.3.5.3 must include maintenance procedures for keeping roof surfaces clean in accordance with manufacturers’ recommendations. In addition, the care needed to promote healthy plant growth and maintain the roof membrane for vegetative terraces and roof systems, as well as replacement procedures of plantings, must be provided. The nonvegetated roof area borders and clearances must comply with provisions of the International Fire Code.®

To comply with IgCC Chapter 7, a project must meet specific mandatory requirements and either the prescriptive option or performance option. Section 701.3.2 On-Site Renewable Energy Systems is a mandatory provision and requires, with two exceptions, a building project design to show allocated space and pathways for future installation of on-site renewable energy systems that could affect the building’s roof if the roof was the designated allocated space.

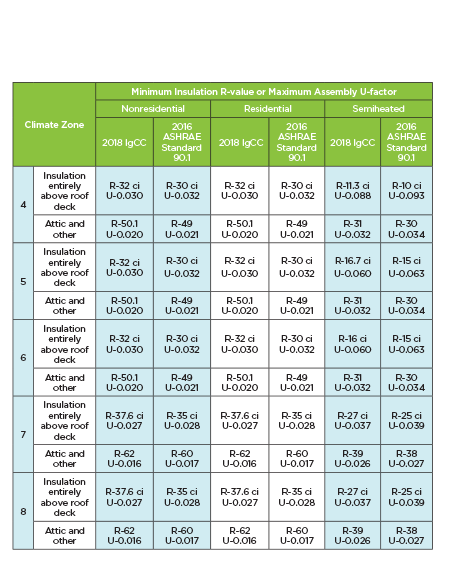

The minimum R-value for roof assemblies is contained in the prescriptive provisions of Section 701.4.2.1 Building Envelope Requirements, which references Standard 90.1. For climate zones 0, 1, 2 and 3, the minimum R-values are published in Standard 90.1. In climate zones 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8, the values are increased as shown in Figure 3. These minimum R-values also are published in informative Appendix E in the IgCC and are not part of the code. For comparison, the minimum required R-values contained in the 2016 ASHRAE Standard 90.1 also are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Minimum R-values for roof assemblies in the International Green Construction Code,® 2018 Edition

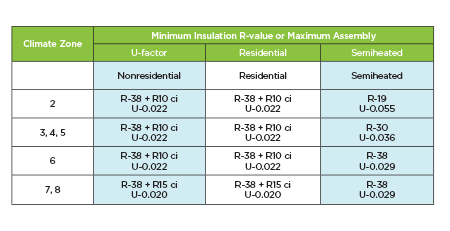

Additionally, Section 701.4.2.2 Single-Rafter Roof Insulation requires single-rafter roof systems (commonly referred to as cathedral ceiling roofs) comply with the requirements of Table A101.1 in Appendix A as shown in Figure 4. These requirements supersede the requirements contained in Standard 90.1.

Figure 4: Table A101.1—Single-Rafter Roof Requirements from the International Green Construction Code,® 2018 Edition

However, Section 701.4.2.8 Building Envelope Trade-Off Option permits a trade-off based on improved performance of the building envelope for the proposed project over a theoretical base design if the requirements previously discussed in Section 701.4.2 are incorporated into the proposed design of the building envelope (roof assembly). The performance option provisions are contained in Section 701.5 and include the requirements contained in Appendix C for renewable, recoverable and purchased energy in addition to building performance calculations. There is one additional compliance path for meeting energy efficiency in the IgCC in Appendix H, which references the IECC prescriptive path. However, Appendix H is informative only (not part of the IgCC) unless specifically adopted by the local jurisdiction.

Chapter 8—Indoor Environmental Quality is likely to indirectly affect roof assemblies. Section 801.4.1.1.1 Minimum Daylight Area requires 50% of the floor area to be in a daylight area. There are multiple ways to produce the daylight area for the floor, including skylights, roof monitors and windows. Therefore, depending on a building’s dimensions, providing daylight through the roof assembly may be the option chosen to meet the daylighting requirement. In addition to daylighting, provisions in Chapter 8 include emissions and volatile organic compound requirements for materials, such as adhesives, sealants, coatings and other products. The 2018 IgCC only applies these requirements to products used on a building’s interior and does not apply them to roofing work.

The mandatory provisions in Chapter 9—Materials and Resources have requirements that will affect new roof system installations as well as roof system replacements. In Section 901.3.1.1 Diversion, a minimum of 50% of nonhazardous construction and demolition waste material generated before the issuance of the final certificate of occupancy must be diverted from disposal in landfills and incinerators by reuse, recycling, repurposing and/or composting. Not included in the calculation is excavated soil, land-clearing debris and waste-to-energy incineration.

All diversion calculations will be based on either weight or volume, but not both, throughout the construction process. However, reuse can include donation of materials to charitable organizations; salvage of existing materials on-site; reclamation of products by manufacturers; and return of packaging materials to the manufacturer, shipper or other source for reuse as packaging in future shipments.

For new building projects on sites with less than 5% existing buildings, structures or hardscape, Section 901.3.1.2 Total Waste requires the total amount of construction waste generated before the issuance of the final certificate of occupancy on the project not to exceed 42 cubic yards or 12,000 pounds per 10,000 square feet of new building floor area. This requirement applies to all waste, whether diverted, landfilled, incinerated or otherwise disposed. The amount of waste must be tracked throughout the construction process in accordance with the construction waste management plan.

Before issuance of a demolition or building permit, Section 901.3.1.3 Construction Waste Management Plan requires a preconstruction waste management plan be submitted to the building owner. The plan must:

- Identify the construction and demolition waste materials expected to be diverted

- Determine whether construction and demolition waste materials are to be source-separated or comingled

- Identify service providers and designate destination facilities for construction and demolition waste materials generated at the job site

- Identify the average diversion rate for facilities that accept or process comingled construction and demolition materials

Separate average percentages shall be included for those materials collected by construction and demolition materials processing facilities that end up as alternative daily cover and incineration.

If Chapter 9’s prescriptive option is selected for compliance, the project is required to comply with any two of the following requirements:

- A minimum of 10% of all permanently installed materials, by cost, for the project must contain recycled or salvaged content.

- A minimum of 15% of the products or materials, by cost, must be manufactured within a 500-mile radius of the project site.

- A minimum of 5% of the materials, by cost, must be biobased products, or have an Environmental Product Declaration or third-party multiattribute certification.

Additional requirements in Chapter 10 include the commissioning and functional and performance testing of a building. Additional informative provisions of the commissioning process are contained in Appendix I. The commissioning process typically is performed by an independent third party to review design documents, installation of materials and systems, and verify performance or compliance testing with the project documents. Chapter 7 requires buildings in all climate zones to have a continuous air barrier; therefore, part of Chapter 10 permits the pressurization testing of the whole building for airtightness. If the building fails the airtightness requirements and the failure point is attributed to the roof assembly, tear-off and replacement may be required to correct the issue.

The future of green codes

If you haven’t been involved with a green rating system project, the IgCC requires documentation before, during and after project completion. Companies that regularly engage in green building rating system projects often employ an individual or team to manage such projects. Currently, the adoption of green codes is not widespread. However, adoption of the 2018 IgCC is likely to occur first in states where some form of a green construction code currently is in place, which include Arizona, California, Colorado, Maryland, Minnesota, Nevada, Tennessee, Texas, Washington and the District of Columbia. Code adoption varies state to state, but typically it occurs one to three (and sometimes up to six) years behind the year of publication of the I-Codes.

If you perform work in a jurisdiction that does not currently have a green code in effect, be prepared for the 2018 IgCC and the additional requirements it may place on your company when performing sustainable work.

Glen Clapper, AIA, LEEP AP, is an NRCA director of technical services.