The roofing industry consistently encounters unique safety challenges. Roofing workers work at heights, contend with unpredictable weather and handle heavy equipment—factors that not only require safety to be a top priority but also a core value.

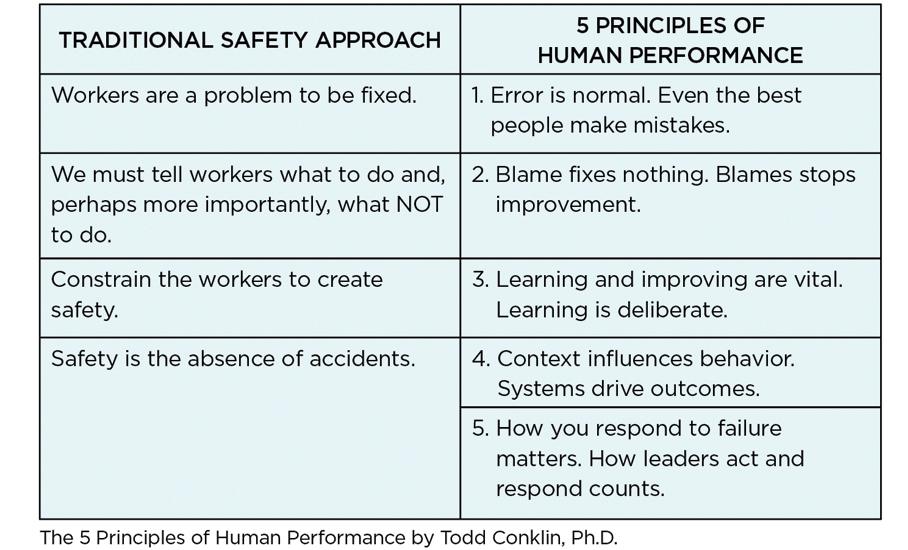

Traditional safety approaches have long focused on enforcing compliance, reducing incidents through penalties and strict rules, and measuring results primarily with lagging indicators such as incidence rates and experience modification ratings. Although traditional methods have value, a shift toward more modern frameworks are redefining the approach to safety and organizational performance.

Traditional method

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics data for 2022, roofing workers had the highest number of fatal work injuries in the construction industry and the second highest of all civilian occupations. Despite decades of traditional safety practices and a downward trend for total recordable injuries, the number of construction fatalities has plateaued for some time, and the trajectory of fatalities in general has remained relatively flat.

The traditional safety approach focuses on identifying and eliminating hazards, enforcing compliance with rules and regulations, and holding individuals accountable for maintaining a safe work environment. This approach assumes most accidents are caused by unsafe acts or violations and places emphasis on personal responsibility and adherence to procedures.

Within the traditional approach to safety, contractors’ safety performance is primarily prequalified and judged by metrics such as the total recordable incident rate. The total recordable incident rate has been the primary safety performance measurement across all industries for the past 50 years. The total recordable incident rate is computed by taking the total recordable injuries from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s Form 300 Log of Work-Related Injuries and Illnesses, dividing it by the corresponding number of worker-hours and multiplying that by 200,000 worker hours (or the equivalent of 100 workers working 40 hours per week 50 weeks per year).

In 2021, the Construction Safety Research Alliance at the University of Colorado at Boulder published a study where researchers examined more than 3.2 trillion worker-hours of data and concluded the total recordable incident rate does not provide a “discernible association” between total recordable incident rate and fatalities and the occurrence of recordable injuries is almost entirely random. Simply reducing the total recordable incidence rate does not directly correlate to reducing the chances of the company experiencing a fatality.

The researchers also concluded the total recordable incident rate is not a precise metric. From a statistical standpoint, when applied to practical circumstances, the total recordable incident rate was found to be invalid statistically for use in comparison with companies, business units, projects and even teams.

The Construction Safety Research Alliance research team found many reasons for their conclusions, including the underreporting of injuries and injury case management. An injury may not be recorded as or rise to the criteria of a recordable incident for an OSHA log, but that does not negate the incident still occurred.

Despite these findings, important decisions at all levels of companies are made based on the total recordable incident rate, including discipline and incentives.

The original intent by OSHA was to assess specific industries. It is a lagging indicator and simply measures numbers of occurrences over time. For example, the total recordable incident rate measures a minor finger laceration the same as a fatality in terms of numbers. These numbers are used throughout the industry as a measure of safety performance and the basis to pre-qualify contractors, bestow awards and even discipline or fire employees.

Although the traditional safety approach provides a strong foundation, integrating it with modern, proactive strategies can create a more effective and adaptive safety management system.

A different strategy

One proactive strategy focuses on human and organizational performance and is a departure from viewing people as a problem to be fixed or managed and shifts it toward viewing them as problem-solvers.

As explained by Todd Conklin, Ph.D., author of “The 5 Principles of Human Performance,” safety is not defined by the absence of accidents but rather by the presence of defenses. In the book, he outlines and applies human and organizational performance principles as an approach to managing safety, productivity and reliability rather than “fixing” workers.

Human and organizational performance involves five principles:

- Error is normal. People are fallible, and mistakes are a natural part of human behavior. Roofing work is no exception. Workers can misjudge distances, overlook small details or experience fatigue. Recognizing errors are inevitable helps roofing companies move from a culture of blame to one of understanding and prevention.

- Blame fixes nothing. Blaming individuals for errors or failures does not improve safety, efficiency or organizational learning. Instead, it can create a culture of fear, discourage reporting and prevent the identification of systemic issues that contribute to mistakes. If people fear punishment, they may hide mistakes, which prevents organizations from learning and improving. A better approach is to analyze why an error happened and use that knowledge to prevent future incidents. Investigating causes, such as training gaps, unclear procedures or unrealistic workloads, leads to meaningful improvement.

- Learning is vital. Often, safety professionals and other leaders are asked to create and enforce rules around a task or process they have never done themselves. But no one can manage well what they do not understand.

Operational learning draws upon the knowledge and experience of those closest to the work in this case, the roofing worker and adding details often missing from never having experienced the task or work firsthand.

Operational learning can:

- Address rules that are prone to deviation.

- Improve or increase defenses that reduce the consequences of human error.

- Identify error traps (conditions or situations that increase the likelihood of human error, such as systemic issues or environmental factors).

Conklin describes an excellent operation as an operation that constantly monitors feedback from normal work and listens carefully to weak signals, recognizing expertise lives at every level of an organization.

In this environment, learning teams are facilitated and include those who do the work and those who design the work with the goal of sharing operational intelligence. The organization takes that feedback and learns from it. Learning teams can be used proactively before an incident or failure and reactively after an incident has occurred. Worker engagement and involvement are key to successful operational learning.

- Context influences behavior and systems drive outcomes. “Context influences behavior” means the environment, circumstances and conditions surrounding individuals significantly affect how they behave. In the workplace, context includes factors such as:

- Work environment: noise, temperature, lighting and ergonomics

- Social dynamics: team culture, leadership style and peer influence

- Task design: complexity of the task, clarity of instructions and time pressure

- Tools and resources: availability, reliability and suitability of equipment

When context is supportive and well-designed, it encourages behaviors that align with safety and efficiency. Conversely, poor context—such as unclear instructions or inadequate tools-can lead to errors or unsafe practices.

Secondly, systems are the interconnected processes, policies, structures and resources within an organization. They shape how work is done and ultimately determine the outcomes, such as safety performance, productivity or quality. Some key points include:

- System design: Flawed systems (such as unrealistic expectations or conflicting priorities) often lead to failures, regardless of workers’ intentions.

- Organizational culture: A culture that values learning and improvement is more likely to produce positive outcomes than one that focuses solely on punishment for mistakes.

- Feedback loops: Systems that incorporate regular feedback and adaptability are more resilient.

Together, these principles suggest individual actions are not solely a matter of personal choice but are heavily shaped by the surrounding environment. Meanwhile, the outcomes of those behaviors are driven by the broader systems in which the individuals operate.

Consider this example of context and culture in the roofing industry:

- Context: A roofing worker might skip safety procedures if working under intense time pressure or extreme weather conditions.

- Culture: If the company prioritizes speed over safety, lacks proper planning or fails to provide adequate training and equipment, unsafe outcomes are more likely.

By understanding and improving context and culture, organizations are better able to influence behavior in ways that lead to safer, more effective outcomes.

- Response to failure matters. How a company responds to failure matters, and how leaders act and respond counts. This principle emphasizes the critical role of organizational and leadership behavior in shaping workplace culture, employee trust and overall performance.

When failures occur—whether safety incidents, operational mistakes or process breakdowns the organization’s response can profoundly affect its culture and future performance. If a company reacts with blame and punishment, employees may become defensive or fearful, leading to underreporting of issues and missed opportunities for improvement. If a company focuses on understanding and learning, it fosters an open environment where employees feel safe to report problems, enabling proactive solutions.

Building trust is critical to success. Employees look to leaders for cues about whether it is safe to speak up, share concerns or propose changes. A supportive response from leaders reinforces trust and promotes more proactive responses, motivating workers to engage actively in problem solving. Leaders who ask the right questions (such as “How did this failure occur?” rather than “Who is at fault?”) help uncover systemic issues and guide meaningful improvements.

Ultimately, how a company and its leaders respond to failure directly influences an organization’s ability to learn, adapt and succeed. A thoughtful, system-oriented approach strengthens resilience while reactive or punitive responses risk undermining trust and long-term growth.

Shifting focus

Applying human and organizational performance to the roofing industry can take several forms.

Worker involvement

Often, frontline workers are the first to spot risks and identify safer ways to perform tasks. By involving roofing workers in safety decisions, leaders can empower workers to voice concerns and suggest improvements without fear of reprisal by establishing anonymous reporting channels or safety committees.

Employers can build trust by recognizing the expertise of seasoned roofing workers, incorporating their insights into safety planning and valuing their contributions in meetings and decision-making.

Additionally, companies can enhance safety policies through collaborative development with workers, ensuring policies are practical and tailored to real-world conditions.

Organizational learning

Roofing companies must create a culture of continuous learning. This involves not only analyzing incidents but also understanding daily successes to refine practices.

Steps to achieving organizational learning include:

- Establishing open communication channels such as dedicated safety hotlines or feedback boxes for reporting near misses, hazards and successes

- Holding regular safety meetings to review lessons learned, share best practices and keep safety top-of-mind for all employees

- Using feedback to drive continuous improvements by revising training, updating equipment and implementing new technologies based on worker input

Training and education

Providing roofing workers with the knowledge and tools to work safely is foundational.

Effective training programs should include:

- Incorporating realistic scenarios to prepare workers for common challenges, such as practicing emergency procedures or navigating rooftop hazards in simulated environments

- Emphasizing the principles of human performance, including error management and mindfulness, to help workers build safer habits

- Promoting a mindset of ongoing learning by offering refresher courses, workshops and certifications to keep skills sharp and knowledge current

Leadership and cultural change

Leadership plays a crucial role in shifting organizational culture. Roofing companies can model their commitment to safety by having leaders consistently follow and advocate for safety practices, showing workers safety is a core value at all levels.

Leaders should prioritize reporting and learning over blame and encourage open discussion about safety without fear of punishment. They also should align the company’s policies and incentives with positive safety behaviors by recognizing and rewarding workers who proactively contribute to safer practices.

Safety first

Embracing the five principles of human and organizational performance can help foster a safer, more resilient industry. These approaches shift the focus from preventing failure to enabling success, empowering workers and creating systems that adapt and improve. With these principles, the roofing industry can move toward a future where safety is not just a rule but a shared value.

CHERYL AMBROSE, CHST, OHST

Vice president of enterprise risk management.

NRCA