During the past 20 years, sporadic reports in scientific literature have suggested a possible link between asphalt fume exposure and respiratory disease. These reports have tended to be confounded by occupational agents, such as coal tar, and lifestyle-related factors, such as cigarette smoking, thereby raising questions about the validity of any links to asphalt fumes.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) also continues to have interest in the respiratory health effects of asphalt fumes and has published a number of scientific investigations and health reviews about the subject.

NIOSH's studies and those of the scientific community have affected the roofing industry—particularly in relation to employee health and safety. But recent studies by Toledo, Ohio-based Owens Corning reveal the effects of worker exposure to asphalt fumes could have been overstated.

Owens Corning's experience

Since it acquired roofing and asphalt plants in 1977, Owens Corning has measured employee asphalt fume exposures through its industrial hygiene air-monitoring program and respiratory disease through its routine mortality surveillance system and medical examination program.

By 2000, enough time had passed and sufficient workplace exposure and health outcome measurements had been taken for Owens Corning to launch two major epidemiologic studies of respiratory disease among its asphalt production and asphalt roofing shingle manufacturing workers.

Following is a report about the two studies. The first study was a joint effort between Georgetown University, Washington, D.C., and Owens Corning to study lung cancer and nonmalignant respiratory disease (NMRD) mortality (death) among active and pensioned employees. The second study was an Owens Corning study of NMRD morbidity (signs and symptoms of respiratory illness) among living, active employees.

Exposures

In 1977, Owens Corning acquired the Lloyd A. Fry Roofing Co., Summit, Ill., and its subsidiary Trumbull Asphalt Co. Trumbull Asphalt buys asphalt from many refineries using a myriad of crude sources and modifies the asphalt by blending and oxidizing it to meet roofing specifications. Trumbull Asphalt also has been involved in paving, cutback asphalt and polymer modification for many years.

Asphalt fume exposure in Trumbull Asphalt's plants occurs primarily during truck loading, tank gauging and pouring hot asphalt into containers. Several changes during the past 30 years dramatically have reduced workers' exposures to asphalt fumes in Trumbull Asphalt's plants.

For example, environmental regulations and active odor reduction have led to fume collection and incineration from most of Trumbull Asphalt's asphalt storage tanks and loading racks. In addition, safety improvements have moved workers several feet further away from pouring streams when filling containers, and quality initiatives have led to reductions in pouring temperatures.

A crude explanation of the asphalt shingle production process is that a fiberglass mat is coated with a mixture of asphalt and mineral filler; mineral granules then are applied to the fiberglass mat's surface to provide ultraviolet protection and an aesthetic appearance; mineral dusting is applied to the back as a release agent; an asphalt sealant line is applied; and shingles are cut to size and packaged.

When an organic mat rather than a fiberglass mat is used, a step is added to saturate the mat with an unfilled asphalt before coating. When laminated shingles are produced, there are additional steps during which an adhesive is applied to shingle parts that are laminated together.

Asphalt fume exposure in these plants mainly occurs at the saturator and coater in organic shingle operations. Changes in these plants that have reduced workers' exposures to asphalt fumes include changing from organic felt-based shingles to fiberglass mat-based shingles, which eliminated the need for the saturator section of the roofing line; installing improved hoods over the coater and cooling sections of the process to remove asphalt fumes; and a trend toward cooler filled-coating temperatures.

Methods

Histories of buildings, processes, jobs, equipment, materials, engineering changes and other parameters were developed for the roughly 30 asphalt production and roofing manufacturing facilities Owens Corning operates. The histories served as a first step in defining unique process-job groupings and designing a quantitative exposure matrix that describes recent and past occupational exposures by job, year and airborne contaminants.

Objective measurements of employee exposure were developed from Owens Corning's industrial hygiene air-monitoring database. The database contains air-sampling results from employees' time-weighted-average exposures in roofing and asphalt production plants from 1977 through 1999.

The airborne contaminants sampled most frequently and systematically over time and of greatest interest for this study are total particulate in the air (more than 1,900 samples); asphalt fumes (more than 1,000 samples based on the benzene- or cyclohexane-soluble portion of the total particulate); and respirable crystalline silica (more than 1,100 samples).

From Owens Corning's personnel files, a detailed work history was developed for each asphalt roofing manufacturing employee and asphalt production employee. This work history captured the process and job an employee was performing at the time of his latest medical examination (for workers who were part of the morbidity study), as well as an employee's lifetime work history by plant, work area or process, job title and date.

Personnel files also were a source of basic demographic information, such as birth date, sex, ethnic group and highest level of education achieved. For deceased individuals who were part of the mortality study, work history and demographic information were supplemented by telephone interviews with retirees and next of kin.

More than one dozen unique process-job categories were defined for the asphalt production and roofing shingle manufacturing plants. These groups incorporated information from the historical environmental reconstruction, industrial hygiene air-monitoring database and employee work histories. Based on consideration of dates of process changes (such as the elimination of saturators in 1982), exposure trends and data availability, it was decided by the investigators to divide the years between 1977-99 into four time periods: 1977-82, 1983-88, 1989-94 and 1995-99.

Once the process-job and time-period groups were finalized, all processes and jobs in the employees' work histories and industrial hygiene sampling data were mapped into these categories.

A quantitative exposure matrix then was developed by which arithmetic mean exposures were estimated for each unique process-job category by time period and airborne contaminant combinations.

Because no quantitative exposure records existed for the pre-1977 period, three plausible scenarios were used that quite likely bracket the actual but unknown pre-1977 exposures: the same exposure levels as in 1977-82, twice the exposure levels as in 1977-82 and half the exposure levels as in 1977-82.

The studies' designs

The mortality study followed a matched case-control design with two case series: one for lung cancer deaths and another for NMRD deaths. Both case series were selected from Owens Corning's asphalt roofing shingle manufacturing and asphalt production workers who had died while active or were pensioned employees during 1977-97.

The lung cancer case series consisted of 39 male deaths. The case series for NMRD deaths included 28 males. For each case series, a maximum of four gender-, year-of-birth- and race-matched controls were selected from the same roofing and asphalt facilities. Cigarette smoking histories were determined from medical records and telephone interviews with retirees and next of kin.

The NMRD morbidity study also followed a case-control design but with important differences. It focused on Owens Corning's employees in the company's U.S.-based roofing, asphalt, insulation and composites manufacturing plants who met the following criteria: employees who completed two or more company physical examinations in addition to the new-hire physical examination; employees whose most recent exams were completed during 1993-2000; and employees who had two or more of these exams entered into the company's medical exam tracking database. Multiple case series were defined according to the signs and symptoms recorded in active employees' voluntary medical examinations.

Medical questionnaires completed during the routine medical examinations provided information about respiratory symptoms and potential confounders, such as smoking. Respiratory symptoms, such as a usual cough, cough with phlegm, wheezing, shortness of breath and asthma, were used to define several case series. Symptoms of eye, nose or throat irritation that occurred only while at work formed the basis of other case series. Case series also were defined according to results of routine pulmonary function testing and chest X-rays.

Results

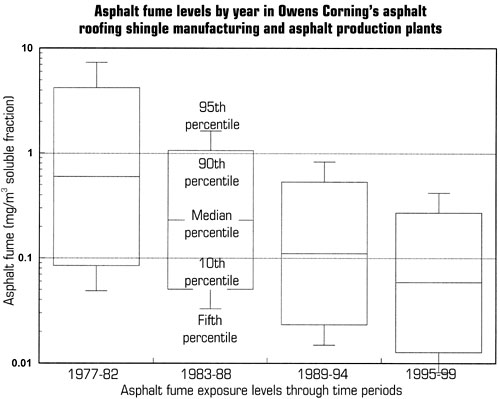

The industrial hygiene data showed clear trends toward decreasing exposures with time (see Figure 1). From the earliest period (1977-82) through the most recent period (1995-99), asphalt fume exposures have decreased tenfold with median exposures dropping from 0.6 mg/m³ to 0.06 mg/m³.

Figure 1: Industrial hygiene data show clear trends toward decreasing asphalt fume exposures.

Likewise, the highest asphalt fume exposures, as measured by the upper 90th percentile of the exposure distribution, decreased more than tenfold from 4.2 mg/m³ to 0.3 mg/m³. These improvements coincided with process improvements previously discussed to reduce exposures in roofing and asphalt facilities.

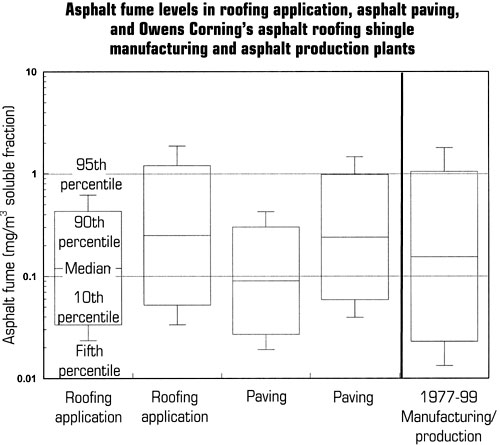

Figure 2: Asphalt fume exposure levels in built-up roofing, paving and manufacturing/production applications.

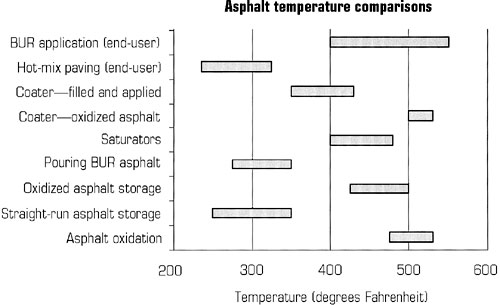

The measured asphalt fume exposure levels in Owens Corning's plants overlap the range of exposures observed in end-user built-up roofing (BUR) applications and hot-mix paving operations (see Figure 2). The higher asphalt temperatures in Owens Corning's asphalt and roofing plants are similar to those observed in end-user BUR applications (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Asphalt temperatures in asphalt and roofing material plants are similar to those observed in built-up roofing (BUR) applications.

After accounting for employee age, cigarette smoking was the strongest predictor of lung cancer and NMRD mortality in workers. A history of cigarette smoking increased a worker's risk of dying from lung cancer 10 times and increased a worker's risk of dying from NMRD nearly seven times. Mortality from lung cancer and NMRD was unrelated to occupational exposures to asphalt fumes—no continuously increasing dose-response relationships between cumulative asphalt fume exposure and mortality risks were observed.

Signs and symptoms of NMRD morbidity were not related to occupational exposures to asphalt fumes. Cumulative exposure, average exposure and most recent exposure to asphalt fumes showed no graded dose-response relationship to the various measures of NMRD.

Respiratory symptoms (such as a usual cough, wheezing or shortness of breath) and respiratory signs (such as impaired pulmonary function or abnormal chest X-ray) were best explained by employee demographics, lifestyle and other medical conditions unrelated to the workplace. Indications of acute irritation, such as self-reported eye, nose or throat irritation, "occurring only at work" were unrelated to asphalt fume exposure at the workplace at the time of medical examination.

Significance and implications

The mortality study considered lung cancer and NMRD deaths among workers in Owens Corning's asphalt and roofing plants and related it to cumulative exposure to asphalt fumes. The morbidity study focused on worker health as determined from routine physical examinations and related it to lifetime average, lifetime cumulative and acute asphalt fume exposure. Neither study found a significant effect on worker health from asphalt fume exposure.

These studies had a number of strengths relative to many earlier studies of asphalt fume-exposed workers. Unlike many previous studies, the studies of Owens Corning workers were not confounded by prior occupational exposures to coal tar. With few exceptions, work histories and cigarette smoking histories were available. High-quality data also were available to develop a quantitative rather than qualitative exposure assessment to asphalt fumes and other common airborne contaminants, such as respirable crystalline silica. This exposure assessment was based on measured rather than modeled results and personal rather than area samples.

Average and cumulative exposures to asphalt fumes through the early 1980s were relatively high in Owens Corning's plants compared with those in other asphalt studies, so if asphalt fumes had been a respiratory health hazard, there was the opportunity for the hazard to be detected in Owens Corning's workers.

These health studies describe results in what we believe are typical asphalt production and shingle manufacturing facilities with respect to exposure levels and various asphalt sources and temperatures. Furthermore, there are marked similarities in asphalt exposures, sources and temperatures among Owens Corning's plants and other asphalt industries, such as paving and BUR applications. These studies reveal something about asphalt's health risks in other industries where similar studies are more difficult and perhaps not feasible.

The studies of Owens Corning workers address the following research needs identified by NIOSH in its latest Hazard Review Document:

- Epidemiologic studies of cancer and noncancer mortality and morbidity that include careful characterization of past and current worker exposures and consideration of potential confounders, such as smoking and coal-tar exposure

- Quantitative risk estimates and establishment of exposure-response relationships

- Studies in which representative samples of exposure levels are evaluated in workers exposed to asphalt-based products

- A test for acute effects

During the next few years, International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) will re-evaluate published, peer-reviewed health data associated with exposure to asphalt fumes and issue a new classification. IARC currently designates asphalt as a Group 3 agent—one that is "not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity" in humans. Typically, IARC classifications are considered by regulatory agencies in their rulemaking. Whether the classification changes or stays the same, roofing contractors can be confident safe work practices and engineering controls will allow roofing asphalt to be used safely. It is expected IARC will consider the epidemiology studies of Owens Corning workers during its deliberations and hearings.

Also, future deliberations by NIOSH about recommended asphalt fume exposure limits and the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists about asphalt fume threshold limit values most likely will take the epidemiologic studies of Owens Corning workers into account.

Bill Fayerweather is Owens Corning's director of epidemiology and data-management systems, and Dave Trumbore is Owens Corning's and Trumbull Asphalt's director of science and technology.