The controversy surrounding the potential cancer-causing effects of asphalt fume exposures experienced during hot roofing work has existed for almost 35 years. But the debate recently took a positive turn with the publication of a quantitative risk assessment (QRA) of asphalt roofing fumes. The assessment was sponsored by NRCA, the Asphalt Institute (AI) and Asphalt Roofing Manufacturers Association (ARMA), who are partners in the Asphalt Roofing Environmental Council (AREC).

Background

In October 2011, a panel of 16 scientists convened by the World Health Organization's International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) found "occupational exposures to oxidized bitumens and their emissions during roofing are probably carcinogenic to humans (Group 2A)."

Although NRCA and its partners believe IARC's finding was wrong, the result was not all that surprising given the policy orientation of government scientists about the assessment of workplace and environmental health hazards. About a decade before IARC announced its findings, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) found "roofing asphalt fumes" to be a "potential occupational carcinogen." IARC declared a number of everyday exposures to be possible, probable or known carcinogens, including coffee, alcohol, cell phones, caffeic acid (a compound present naturally in a wide variety of fruits and vegetables), and, in November 2015, red meat and processed meats such as hot dogs and bacon.

Similar to the NIOSH evaluation before it, the IARC finding is based on skin-painting studies conducted on laboratory mice and studies of roofing workers that found increased rates of cancer in the lung, upper respiratory and digestive systems. However, IARC and NIOSH found the human studies were compromised because of "confounding" exposures to coal tar, asbestos and tobacco.

Independent analyses of the studies have found the confounders might explain the excess cancers in these studies. The upshot is both findings rest critically on studies conducted on lab mice. This is one reason NRCA believes the evidence is insufficient to support a definitive finding a cancer hazard exists. In fact, around the time of the NIOSH finding, another widely respected scientific group, the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH), determined asphalt fumes are "not classifiable as a human carcinogen."

Quantitative risk assessment

It is important to recognize findings such as those from IARC and NIOSH are, using the vernacular of regulatory scientists, hazard determinations, not risk determinations. As IARC explains in the monograph it published about asphalt: "[IARC] Monographs identify cancer hazards even when risks are very low at current exposure levels."

This distinction can make all the difference when it comes to the practical ramifications of a hazard determination. As the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) has explained, a hazard finding identifies "the potential of a substance to cause human health effects" such as cancer. It means, therefore, only that exposure to the substance entails "some" risk.

On the other hand, a QRA (which is an estimate of how many cancers will occur in a population exposed to a substance) enables us "to discriminate between important and trivial [risk] threats."

NAS has observed the need to quantify risk is more important when animal data form the basis for a hazard determination because animal studies typically use unrealistically high doses "to maximize the sensitivity of the study for determining whether the agent being tested has carcinogenic potential."

Since the 1980s, QRAs have been an integral part of regulatory decision making for good reasons. Controlling exposures typically is an expensive proposition. Spending finite resources to address inconsequential risks inevitably dilutes funding for and attention spent on other, much greater ones—the consequences of which can leave workers exposed to real hazards. This is a high price to pay for chasing tiny, theoretical risks.

In the case of occupational health standards, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) long ago made the risk concept a key part of its framework for deciding whether and to what extent a hazard should be regulated. OSHA defines work-life risks of one-in-a-thousand to be "significant risks" calling for controls on exposure if feasible. Lower risks are too small to regulate.

As a consequence, even if the IARC and NIOSH findings are taken at face value, a quantitative estimate of risk is needed to determine whether the potential cancer threat is great enough to warrant action to reduce it.

What did the risk assessment find?

In light of these considerations, NRCA and its AREC partners asked Lorenz Rhomberg and a multidisciplinary team at Gradient, Cambridge, Mass., a leading environmental and risk sciences consulting firm, to develop a risk assessment consistent with the methodologies used by health regulators. With extensive experience at Harvard's School of Public Health and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Rhomberg is a leader in the field of risk assessment and has been selected to serve on a number of blue-ribbon NAS scientific panels to study emerging issues. Rhomberg and Gradient work for clients in all parts of the political and risk policy spectrum.

By using a scientific team with a strong reputation for independence and expertise and directing the Gradient team to develop an assessment based on methodologies consistent with those of EPA, AREC's objective was to maximize the chances the QRA will be well-received in scientific and regulatory circles.

Gradient concludes: "The weight of epidemiology evidence [i.e., human studies] does not support roofing asphalt as a risk factor for lung cancer because, among other things, the increased cancer rates found in some of these studies may 'be attributable to coal tar, asbestos, smoking, or another factor.'" Gradient also finds studies in humans show "no significant association between roofing workers' exposures and the development of skin cancer."

Therefore, the risk assessment reinforces the conclusion that emerges from the NIOSH and IARC evaluations, namely that skin-painting studies of laboratory mice represent the principal basis for finding a cancer hazard. It also suggests the human studies, which scientists and regulators acknowledge are the far better measure for assessing human health hazards, are at best difficult to reconcile with the results of the mouse studies.

Gradient also finds, assuming a cancer hazard exists at all for roofing workers exposed to asphalt fumes, the risks are relatively low. Specifically, for lung cancer (the type of cancer most commonly thought to potentially be associated with roofing worker exposure to asphalt fumes), Gradient estimates the work-life risk ranges from two chances in 1 billion to eight chances in 1 million.

Although studies of workers do not show a skin cancer hazard for roofing workers, Gradient nevertheless developed a range of estimated work-life risks for this cancer type, as well. The estimate based on the best data is three chances in 10,000.

As is customary for risk assessments, Gradient includes a detailed uncertainty analysis evaluating factors that might render the estimates too low or high. The following factors stand out:

- The estimates are based on animal studies. Although regulators typically assume animal results are relevant to humans (as the IARC and NIOSH evaluations illustrate), the human studies do not indicate, as Gradient finds, that asphalt roofing work is a risk factor for cancer.

- The estimates use OSHA assumptions for quantifying risks over a "work-life." Thus, they assume worker exposure to asphalt roofing fumes for eight hours per day, 250 days per year for 45 years. Such an exposure scenario is not entirely impossible but clearly overstates risks for an overwhelming majority of roofing workers.

- There is considerable scientific evidence that shows polynuclear aromatic compounds (the substances believed to be responsible for the tumors seen in mouse studies) pose little or no skin cancer risk in humans.

Because the risk estimates are well below OSHA's regulatory floor, Gradient finds that overall, the various methods indicate cancer risks to roofing workers from dermal and inhalation exposure to built-up roofing asphalt are within a range typically deemed acceptable within regulatory frameworks.

The Gradient risk estimates assume daily full-shift exposure to the current ACGIH "threshold limit value" (TLV) of 0.5 milligrams per cubic meter of air (0.5 mg/m3), the only nationwide recommended exposure limit for asphalt fumes. (OSHA has not set a permissible exposure limit for asphalt fumes.) Although the TLV is intended to protect workers against mild, reversible irritation of the eyes and upper respiratory tract, Gradient finds the TLV is "adequately protective" for potential cancer effects, as well.

What it means

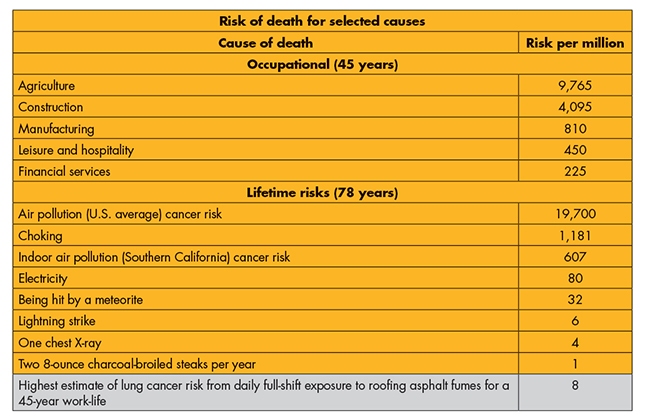

The concept of risk can be complicated. What does a lung cancer risk of eight chances in 1 million mean to a roofing worker? One way to put the numbers into perspective is to compare them to other occupational risks and to risks that are a part of everyday life. The figure on page 32 provides some examples.

As the figure shows, using the high end of Gradient's risk range for lung cancer:

- A hot asphalt roofing worker who switches to an office job would have a risk of death that is about 30 times greater than the asphalt-related lung cancer risk associated with his or her previous job.

- The cancer risk of breathing average outdoor air in the U.S. is about 2,500 times greater than a roofing worker's asphalt-related lung cancer risk. The risk of breathing indoor air in Southern California is about 75 times greater.

- The asphalt roofing lung cancer risk is comparable to or lower than the lifetime risks of death from choking, being hit by a meteorite, a lightning strike, a single chest X-ray and consuming two charcoal-broiled steaks per year.

Further perspective can be gained by examining the number of cases of lung cancer that would occur if roofing asphalt fumes are carcinogenic. With hot-applied asphalt roof systems accounting for about 7.3 percent of the low-slope market, the risk assessment predicts exposure to asphalt roofing fumes would lead to 0.001 lung cancer cases annually based on the high end of the range developed by Gradient.

|

Looked at another way, the QRA projects that during the next 750 years, a single case of lung cancer may occur among low-slope roofing workers (assuming the population and asphalt exposures remain static). As a practical matter, the risk is zero.

What about other products?

The news is even better when it comes to other asphalt roofing products. Specifically:

- Soft-applied polymer-modified bitumen products (those applied with torches or hot-air welders): The U.S. data indicate inhalation exposures to fumes typically are nondetectable and well below the TLV in all cases. Risks (if any) from inhalation and dermal exposures are, therefore, expected to be well below those assessed for hot-applied products.

- Cold-applied products (shingles, self-adhering and cold-applied polymer-modified bitumen, cold-process built-up roofing asphalt, underlayments): These products do not emit fumes and involve no inhalation exposure. There is no evidence of dermal absorption.

- Cutback and emulsified coatings and sealants: These products do not emit fumes. Although dermal contact occurs, there is no evidence absorption rates would exceed those of condensed fumes which, as Gradient found, pose no significant worker cancer risk.

- Tear-offs: There is no scientific evidence inhaling asphalt particulates poses a cancer hazard. Available data for low-slope tear-offs indicate inhalation exposures to asphalt particulates average about half the TLV for fumes and, therefore, as Gradient found, are "adequately protective" against any cancer hazard. In the case of steep-slope materials such as shingles, exposures are expected to be much lower because of the use of manual prying or slicing tools. A recent study found asphalt particulate exposures during shingle removal jobs were nondetectable. With respect to dermal exposures, Gradient found the skin cancer risk from asphalt particulates during low-slope tear-offs to be well below OSHA's regulatory floor. Dermal exposures during steep-slope tear-offs certainly are much lower.

The takeaways

The big picture message is asphalt roofing products can be installed safely by roofing workers and, by extension, are safe to other workers and the general public whose exposures are far lower. In this regard, it is useful to recall the narrow scope of the IARC and NIOSH findings, which apply only to occupational exposure during roofing work. They neither classify any asphalt roofing product as a cancer hazard nor apply to homeowners, other building owners and/or managers, building occupants, consumers or the general public who may have contact with or exposure to asphalt roofing products or fumes. The findings' primary focus was on hot-applied products where exposures, though higher, pose risks that are theoretical and inconsequential.

Despite Gradient's findings, the asphalt fumes saga is likely to continue. As a consequence of the IARC monograph and other factors, additional reviews are expected by a number of regulatory and scientific groups, including the National Toxicology Program, ACGIH, California's Proposition 65 and Cal/OSHA. NIOSH and OSHA might take action though this is far less certain. Although NRCA has not seen movement on these fronts, additional reviews are likely in the coming years.

The risk assessment may positively affect future regulations in two ways. First, all these groups have busy agendas, and the small risks estimated by Gradient might persuade them to assign a lower priority to the asphalt fumes issue. Second, several of these groups set recommended or legal exposure limits for workers. As discussed, the Gradient work supports the conclusion that limits lower than the TLV are not needed to protect against potential cancer hazards.

Although average fume exposures during hot asphalt roofing work are, on average, at or below the TLV, published data show higher exposures can occur for kettle operators and workers on roofs. Eliminating the practices that lead to these higher exposures would significantly boost prospects for delaying further reviews and achieving good results if and when regulators take action. More important, it would reduce potential health risks, minimize odor complaints and improve working conditions. Recently, NRCA has taken two actions to address this concern.

First, NRCA and ARMA proposed revisions to ASTM D312, "Standard Specification for Asphalt Used in Roofing," to reduce kettle temperatures by setting a 550 F maximum temperature; lower asphalt application temperatures by setting maximum equiviscous temperatures (EVTs) for Type III and Type IV asphalts; and provide accurate labeling of asphalt products, including the new maximum kettle temperature and lot-specific EVT values. These changes were adopted and are published as ASTM D312-15. Lowering temperatures has a powerful influence on fume exposures: A 50 degree Fahrenheit reduction in temperature cuts exposures in half.

Second, NRCA is working with ARMA to update their joint best practices recommendations for reducing fume exposures to incorporate the revised ASTM International standard and other developments.

The industry recommendations for good temperature management and other work practices to control fume exposures would go a long way toward achieving uniform compliance with the TLV across the roofing industry, but this depends on making these practices a routine part of hot asphalt roofing in the field. To better protect the health of roofing workers and improve working conditions, contractors should make these simple work practices a priority and recognize the need to effectively train workers so these practices become an integral part of every hot asphalt roofing job.

Focus on the work

After 35 years of study, millions of dollars spent, and countless hours of association volunteer and staff time invested in the question, "Is worker exposure to asphalt fumes carcinogenic?", the short answer is, "No, but … ." The "but" is because fume exposures during hot asphalt roofing operations can exceed recommended levels; it remains important to provide adequate training to make proper work practices an integral part of hot roofing work and keep exposures to a minimum.

That said, the Gradient risk assessment is a positive development for the roofing industry. The foresight and tenacity of NRCA, ARMA and AI to thoroughly research the health effects of working with asphalt roofing products is unprecedented and speaks to the industry's commitment to worker health and safety.

Thomas R. Shanahan, CAE, is NRCA's vice president of enterprise risk management.