Being smart about applying a roof coating is the responsibility of the coating applicator in the field. This may be blunt, but the applicator is the last line of defense to make sure a surface is ready before a coating is applied to it.

In nearly 20 years of formulating coatings, I have experienced or read about instances where an angry contractor has called a manufacturer wondering why a coating is not adhering to the surface. The fact is: The coating is sticking exactly how it is supposed to on the surface to which it was applied. Unfortunately, what is beneath a coating may not be suitable to promote the necessary adhesion to keep it in place, resulting in unwanted headaches, angry telephone calls and future problems.

A properly adhered coating begins with a properly prepared surface. All the formulating, testing, field trials, etc., are of minimal use if the substrate is not treated with the same care and attention paid to applying the new coating.

It's about contact points

At its simplest level, the key to coating adhesion can be summed up in two words: contact points. If a mineral-surfaced polymer-modified bitumen sheet were magnified and viewed along its edge, we would observe countless ridges and valleys. We would see the same profile in a sanded piece of wood before painting. Woodworkers know these peaks and valleys in the sanded wood provide the coating with more "teeth," or contact points, for the paint or varnish to adhere to than the same piece of wood sanded smooth. The same is true with a roof surface.

For surfaces that are not as visibly "rough," such as single-ply membranes or metal, the surface chemistry still determines whether certain coatings will adhere. For example, in coatings terms, TPO membrane surfaces do not promote adhesion in a wide range of coatings. This is why solvent-borne coatings work better on TPO membranes—the solvent swells the TPO polymer and allows some of the coating's polymer to diffuse, or flow, into the top layers of the TPO membrane. Metal surfaces that are visibly smooth can have a factory-applied powder coating, electroplating process or galvanizing treatment that, though smooth in appearance, can be receptive to certain coatings such as polyurethanes or two-part amines.

Sometimes, the surface chemistry only is receptive to a specific coating type. For example, silicone coatings when cured arrange their polymer chains in such a way the silicone (carbon-silicon) groups face the "top" of the coating at the coating/air interface. These hydrophobic (water-repelling) groups are not receptive to adhering anything other than another silicon-containing product. Determining whether the coating will be applied over a silicone-coated roof is important before making a decision regarding the type of coating going over it.

When possible, a rough surface is desired because of the increased surface area and greater number of contact points. For mineral roof surfaces, this is not difficult because the minerals already create a rough surface. For smooth-appearing surfaces such as single-ply surfaces, once cleaned, solvent-wiping with acetone or alcohol will remove oxidation and swell the polymer at the surface. In addition, metal surfaces can be abraided mechanically with a grinder or garnet abrasive to provide additional contact points that help adhesion.

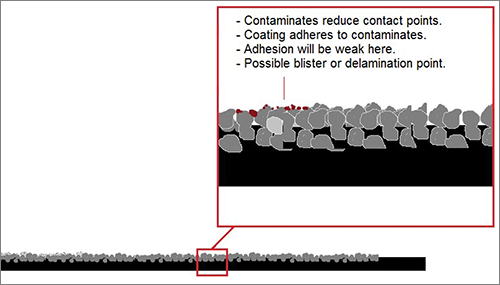

Photos courtesy of The Garland Co. Inc., Cleveland. Surface contaminates reduce contact points and can lead to coating delamination. |

If a contaminate is present on a rough surface, a coating may adhere to the contaminate and not the intended surface at that specific point. A contaminate can be anything: dust, dirt, bird droppings, water, fungus, algae or even an existing coating.

Any interruption of the continuity of the coating and substrate interface, however small, can be detrimental to the bond integrity over the coating's life. The goal of surface preparation is to give a roof coating as many contact points as possible and the best opportunity to perform as intended.

Following is a list of common bond-breaker problems and ways to improve contact points and enhance adhesion. This is not a complete list; many contractors will encounter problems not discussed here. But the list helps begin the process of thinking about the problems not mentioned. The common theme is each of these problems breaks the continuity of the coating and surface interface, reducing contact points, and ultimately resulting in adhesion issues and reduced service life.

Additionally, I recommend applicators take advantage of the knowledge trained roof coatings professionals can offer because they know the coatings best and will suggest the best way to adhere coatings properly the first time.

Common problems and solutions

PROBLEM: End lap or seams opened

Fish-mouthed open seams (see Photo 1) are ways for water to enter underneath a membrane and between the coating and

surface interface by creating an unprotected edge. Even if the gaps are small, a water molecule is much smaller, and

these openings cannot be fixed by putting a coating over them no matter how thick it is applied.

SOLUTION: Open seams should be repaired using similar materials and recommended roofing practices.

Photo 1: Fish-mouthed open seams need to be addressed before coating. A coating never will be a suitable substitute for proper repairs. |

PROBLEM: Wet insulation or sublayer

In some situations, the surface feels dry but may be holding pockets of wet insulation beneath. Unfortunately, there

is no way of knowing—throughout the day—whether that water will flow through some point of ingress on the

roof surface. Upon coating, the coating acts as a barrier and the water pushes the coating off the roof surface from

behind.

SOLUTION: An infrared scan of the roof before coating will identify wet areas that can be removed and corrected ahead of coating. This also could be an opportunity to address poor drainage in areas and build up the surfaces to direct water to the drain.

PROBLEM: The weather

Part of preparing a roof for a coating is knowing the environmental condition of the roof not only before the coating

is applied but also a few days after the coating is applied. Remember, unless a fast-curing coating, such as a

two-component polyaspartic or polyuria, is being applied where cure times are measured in minutes or less, a typical

roof coating will achieve full strength in hours or days.

During this process, though the physical work of a contractor may be done for the day, the coating is busy curing or drying and is susceptible to all the problems that could have plagued it during application. Even the best surface preparation and application performed on an ideal sunny day could go wrong if something as unassuming as the dew point comes close to the coating's surface temperature during its setting time. The dew point is the temperature at which no more water can be put into the air. When the surface temperature and the dew point approach each other, the water in the air must condense on a surface. Dew usually happens on cooler nights, especially when the day has been humid. This is where careful study of the weather can be a great benefit.

SOLUTION: As a roofing contractor, you are an amateur meteorologist. Take time to learn about basic weather terminology and find a trusted, accurate weather source such as www.noaa.com or Wunderground to provide detailed 48-hour forecasts. Aside from the obvious forecast of rain, pay close attention to numbers such as dew point and falling atmospheric pressure, which indicate a future rain event. Wait until later in the morning to perform work to ensure morning dew has completely dried or manually remove dew via a leaf blower or squeegee to channel water to drains or scuppers. Similar to dirt and grime, water is a contaminate on a roof surface that will interrupt the continuity of the coating and surface interface, reducing contact points.

PROBLEM: Ponded water

This problem also could be filed under "same roof, different surface," but because it is so prevalent, it deserves

its own section. Roofs are designed to move water off themselves as quickly as possible. As ideal as this concept is,

the reality is ponded water is an unavoidable fact of life. Whether caused by poor building design, improper drainage

caused by elevation differences, lack of maintenance on HVAC units dripping rusty condensate in an area, or external

variables such as wind or varying snow loads, identifying ponded water areas before coating is critical to a

coating's success. (It should be noted this does not include short-duration ponded water, such as after a rainstorm.

These instances are considered acceptable by roofing manufacturing associations. However, ponded water that remains

for more than 48 hours can cause problems for roof coatings.)

SOLUTION: Ideally, drainage should be addressed before a coating is applied. However, this cannot always happen, such as when a restoration coating is applied to an existing roof. In situations where the drainage cannot be addressed, the first thing to do is realize the surface under the ponded water is going to have a lot more dirt, grime and other microbes, spores, etc., than drier areas.

So the approach to cleaning these surfaces should be more aggressive than what would be done to drier areas. If the drier areas are going to be treated with a pressure washer, the ponded water areas should get more than a pressure washer treatment, such as bleach solution, Simple Green,® or ZymeAway,® followed by a vigorous scrubbing, thorough rinse and dry.

The key here, beyond the equally important choice of coating, is to do more with preparing these low areas than the drier portions of the roof. Unfortunately, standing water areas are a bane to roofing contractors because—despite the best preparation and because of its nature—water wreaks havoc on roof coatings though some degrade faster than others. There is no perfect coating. However, a roof coating stands a fighting chance at a longer service life if the coating is allowed to fully envelop the intended surface and not the "stuff" left from the ponded water. Also, be sure to follow federal, state and local laws governing gathering and disposing of rinse water. Drying the cleaned surface also is crucial to remember because water is a bond breaker.

Photo 2: Power washing a roof is a great way to remove dirt and grime, but if the water does not go to a drain and sits in a low spot, the coating will be subjected to the same ponded conditions once installed. |

PROBLEM: Fungus and algae

Fungus and algae are present anywhere there is water, sun (warmth), a food source and something to sit on; ponded

water can provide all this. Fungus and algae take full advantage of the sun-soaked water and propagate on any surface

where the spores can attach, including a roof substrate. The spores eat anything they can, including the calcium

carbonate filler present in many roof coatings. This is why simply spraying the surface with a power washer to remove

surface dirt is not enough, especially where ponded water exists. Sometimes, there are tree branches extending above

the roof or nearby, dropping their spores onto the surface and discoloring the roof.

SOLUTION: As in ponded water situations, it is best to do more than power wash the surface by incorporating a solution of fungus or algae remover, such as ZymeAway or a similar product designed to remove the microbes from the surface and increase coating contact points. As with any chemical that is to be rinsed, be sure to follow federal, state and local laws governing gathering and disposing of rinse water. Again, drying the cleaned surface is crucial.

Photo 3: When power washing is not enough, scrub the surface with a bleach solution (one part chlorine bleach, three parts water) or roof cleaner, thoroughly rinse and dry. |

PROBLEM: Coating over an existing coating

As a result of aging, aesthetics and degradation or as part of a warranty, there may be a time when a coated roof

needs a new coating applied. There is a risk of the new coating, especially a solvent-based one, softening the

existing coating and causing delamination or localized blistering later.

SOLUTION: It is important to realize the adhesion of a new coating only is as good as the existing coating's adhesion to the metal, mineral surface, etc. Knowing what the coating will contact is key to successful adhesion. Secondly, and equally important, the new coating will inherit the issues of the previous coating if the new coating is applied directly to the old coating. With this in mind, it is recommended preparation be given proper consideration. If power washing does not remove all the existing coating, is the risk of not removing the remainder worth the problems later when the solvents in the new coating swell the resin in the existing coating causing delamination? Sanding the residual existing coating on a metal roof helps create a rougher surface (more contact points) and also exposes more of the intended surface for the new coating. If time and budget permit, I recommend including additional means to remove the existing coating as much as possible whether through sanding on metal or using cleaning agents and vigorous scrubbing on a mineral surface, single-ply membrane or metal roof.

Another solution would be to consider using a primer. Primers aid in coating adhesion by providing a bond between the roof surface and coating. It should be noted a primer is never a substitute for proper roof surface preparation, but priming provides a uniform surface for the topcoat with infinite contact points to adhere to while biting into the substrate and existing coating. I recommend you consult coating manufacturers before using primers in any situation.

PROBLEM: Fasteners on a metal roof are missing

Throughout the life of a metal roof, the thousands of screws penetrating the panels, each containing their own

grommets or washers, dry out and crack, leaving holes for water ingress and the opportunity for corrosion to occur.

SOLUTION: It will be too late once a new coating is applied to address this, so it is important to check fasteners before applying a coating. Replace missing fasteners and tighten loose ones. Fix fish-mouthed seams and, if on a horizontal face, install extra fasteners to be sure this doesn't become an issue in the future.

PROBLEM: Vent pipes, protrusions or old lines no longer in use

During a building's life, repairs to the HVAC unit or interior remodeling may close off and render old vent pipes

obsolete. However, the building owner does not remove the pipe or take out the drain lines.

SOLUTION: Consider finding out whether old protruding pipes or unused drain lines could be removed and the surface sealed over, eliminating unnecessary vertical surfaces.

Be prepared

For roof coatings, the surface with the most contact points over the intended surface has an increased service life compared with the same coating applied to a poorly prepared surface. I listed some common bond breakers that interfere with the continuity of a coating-surface interface, reducing contact points. Some solutions are commonsense, but others may not be. A trained roof coatings professional is an invaluable resource before a coating is applied. The point to take home is this: When a manufacturer recommends the surface be free of all dirt, dust, grease and water before coating, do the smart thing and prepare the surface well.

Jason Smith is senior research and development chemist for The Garland Co. Inc., Cleveland.

For an article related to this topic, see "Roof coating forensics," December 2013 issue.

Did you know?

NRCA Guidelines for Roof Coatings provides technical information about the application of various types of roof coating systems, which preparations are necessary for their successful performance and quality control guidelines for on-site evaluation. The guide is available at shop.nrca.net.