In 1994, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) issued Subpart M—Fall Protection in its construction industry regulations. In it were new requirements that were, to say the least, unsettling for the roofing industry. Foremost was the new requirement to provide fall protection whenever a fall distance is 6 feet or more above a lower level. Previously, the trigger height was 16 feet.

Since 1994, the roofing industry generally has adapted to the federal 6-foot trigger height though a number of states, for example California and Oregon, have trigger heights that exceed the 6-foot federal OSHA requirement. Other state-plan states also provide differing fall-protection options from the federal requirements. These regulatory variations contribute to the lack of consensus about which fall-protection options best protect workers partly because there are so many variables on every roofing project to consider.

The dilemma

Shortly after Subpart M was published, NRCA approached OSHA regarding the standard's application to steep-slope roofing work, specifically residential roofing work. OSHA defines steep-slope roofs as those with slopes greater than 4:12 (18 degrees). The roofing industry was concerned fall-protection options for work on steep-slope roofs were too limited and did not provide sufficient roofing worker protection. The regulation only allowed for personal fall-arrest (PFA), guardrail and/or safety-net systems, which OSHA defines as conventional fall-protection options.

However, OSHA included in Subpart M a new provision for residential fall protection that stated if conventional fall-protection methods were either infeasible or created a greater hazard, a site-specific fall-protection plan could be developed where other options such as slide guards or safety-monitoring systems could be used. The provision created a paperwork burden that, practically speaking, made complying with the option impossible (See "Infeasible and greater hazard," page 34, and "Fall-protection plan," page 36.)

Nevertheless, the provision seemed to provide some direction for steep-slope roofing work; however, it was limited to residential roofs though the term "residential" was not defined. Therefore, it was unclear which steep-slope roofs would (or would not) qualify as residential.

During 1995, NRCA, the United Union of Roofers Waterproofers and Allied Workers, and CNA, Chicago, were meeting regularly as a group representing the roofing industry to determine the actual safety concerns regarding steep-slope roof system installations and, in particular, residential applications.

Because Subpart M included appendixes developed by OSHA and one with the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) addressing fall-protection issues associated with framing and other related activities on new homes, the roofing industry group endeavored to develop an appendix that would address fall-protection issues related to roofing work on steep-slope roofs. This was a key distinction.

OSHA defines roofing work as the "… application and removal of roofing materials … but not including … the roof deck." Because Subpart M regulated fall protection for workers working on "steep roofs" and did not specify "roofing work" on steep-slope roofs, an important coverage gap existed. The agency specifically recognized the uniqueness of low-slope roofing work and provided contractors with warning-line and safety-monitor fall-protection options, but no such accommodations for steep-slope roofing work are offered.

As a result, the steep-slope regulation applied to any worker on any steep-slope roof, hamstringing roofing contractors into using conventional fall-protection options that, in many cases, actually put workers at more risk given the unique nature of steep-slope roofing work.

What the roofing industry group wanted was regulatory language that considered the unique fall hazards associated with steep-slope roofing work and provided unique fall-protection options, such as roof jacks with toe boards, otherwise known as slide guards.

At about the same time, NAHB had received negative feedback from its members about Subpart M and met with OSHA about its members' concerns. Shortly thereafter, the language the roofing industry developed to address steep-slope roofing work was subsumed by OSHA into a new compliance directive called the Interim Fall Protection Compliance Guidelines for Residential Construction (interim guidelines), which also had provisions addressing NAHB's concerns.

In the interim guidelines, the term residential construction was finally defined as applying to "structures where the working environment, and the construction material, methods, and procedures employed are essentially the same as those used for typical house (single-family dwelling) and townhouse construction. Discrete parts of a large commercial structure may come within the scope of this directive (for example, a shingled entranceway to a mall) … ." Importantly, the directive allowed the use of slide guards and safety monitors as fall-protection options in defined and limited circumstances and on some commercial structures.

The upside was the roofing industry's concerns had been addressed. NRCA did not want steep-slope roofing work limited only to buildings where humans resided, and the residential definition accommodated this desire. NRCA argued that regardless of a building's use, the key factors for determining fall-protection options should be the type of roof system installed, its slope and its eave height.

The downside was OSHA's approach did not address the roofing industry's overarching concern that Subpart M itself still did not address work on steep-slope roofs.

In OSHA's defense, the guidelines were supposed to be interim and lead to a reopening of Subpart M to address all of NRCA's and NAHB's concerns. Although the interim guidelines went a long way to address the roofing industry's concerns, the roofing industry hoped it could petition for proper steep-slope roofing work representation in the standard when it was reopened. Therefore, at the time, the guidelines were considered a positive development.

OSHA reopened the rule in 1999 but only asked specific questions; it did not address the unique roofing industry issues previously neglected. Nevertheless, NRCA submitted comments, and, subsequently, OSHA decided not to make any changes. So the assumption was that if the interim guidelines would last until Subpart M—Fall Protection was reopened as part of the normal regulatory process, the industry would have the fall-protection options necessary for steep-slope roofing work.

In April 2008, almost 15 years later, NAHB sent a letter to OSHA requesting three things. First, it asked OSHA to withdraw the interim guidelines it previously supported. In its letter, NAHB addressed roofing work specifically, stating: "NAHB believes developing and using a written fall protection plan for these residential construction operations is an acceptable alternative to conventional fall protection measures. We now believe that [the Interim Guidelines] extended the use of fall protection plans to other tasks, trades, and work activities that may no longer be appropriate because, due to the development of new equipment, conventional fall protection may be used. For example, during roofing operations personal fall arrest systems can be used when applying roofing materials such as felt and shingles."

Second, NAHB asked OSHA to define the term residential construction "based on the materials and methods used in construction, regardless of the end use of the structure … and [third, allow] employers to develop and use a standardized fall protection plan … ."

One of NAHB's contentions was the interim guidelines "created confusion in the residential construction industry as to what fall protection methods and systems must be used to comply with OSHA standards."

However, as it pertained to roofing operations, the interim guidelines were quite clear and precise. In fact, the guidelines addressed the three risk areas: height, slope and roof system being installed. There may have been confusion for other trades addressed in the guidelines but not for the roofing industry.

How NRCA's proposal compares with existing regulations

Whereas NRCA agreed in large part with the second and third NAHB requests, it was dismayed NAHB would argue conventional fall protection is suitable for all roof system installations and believed NAHB was outside its area of expertise regarding this matter. Nevertheless, despite NRCA's vocal and frequent requests to the contrary, OSHA, citing NAHB and other groups supportive of the withdrawal, complied with the request in December 2010 and rescinded the interim guidelines.

The interim guidelines were withdrawn with no adjustment made to address issues related to roofing work on steep-slope roofs. So instead of allowing a roofing contractor the flexibility to ascertain the risk associated with roof system removal, installation or repair, OSHA agreed with NAHB and stated conventional fall-protection methods are enough.

OSHA argues specially constructed guardrail systems are suitable for steep-slope use, and some diligent safety professionals have been working on such equipment. To be fair, once design issues are resolved, such systems may have their place in new construction environments where eave guardrail installation can be achieved during the erection of the structure providing long-term protection for a variety of trade activities while a house is built. It is not to say guardrail-type fall protection can never be used for reroofing work, but the option is not yet practical or safe, not to mention cost-effective in reroofing situations (the cost argument does little to persuade OSHA).

However, of the three options, a PFA system is the only practical option for steep-slope roofing work. But PFA systems aren't always the safest choice. Interestingly, OSHA has on its regulatory agenda the development of a new regulation called the Injury Illness Prevention Program Standard that would require a risk-based approach to safety plans where, for example, fall risks are evaluated on an individual project basis. One would think OSHA would agree having choices from which to select safe work practices would be optimal, but that is exactly the opposite of what is happening with steep-slope roofing work.

As a result of rescinding the interim guidelines, NRCA sued OSHA in February 2011 on the premise OSHA did not follow the appropriate rule-making process, support the change by substantial evidence or comply with the Regulatory Flexibility Act that requires certain procedures, such as an economic impact analysis, before regulatory action.

In April 2011, the court ruled against NRCA saying OSHA was within its purview to provide these compliance directives and did not need to go through the regulatory process to implement such changes.

Since the ruling, OSHA and NRCA have met numerous times to discuss ways to implement the original rule that essentially demands the use of only conventional fall protection on all steep-slope roofs.

NAHB's recent move

On Dec. 7, 2012, NAHB sent another letter to OSHA asking the agency to initiate rule making on Subpart M—Fall Protection and replace the residential construction regulation with a new expanded residential section. In its request, the association reiterates many of the points NRCA has made for years, such as the need for regulatory language that reflects the unique nature of the work being performed.

NRCA made this point repeatedly during OSHA's advisory committee meetings and often argued against NAHB. As a result of these deliberations, it became apparent the main difference between NRCA's and NAHB's viewpoints was the issue of new construction vs. reconstruction activities. This led to subsequent discussions about the work each association's members perform; namely that roughly 80 percent of NAHB members' work involves new construction activities, but nearly 80 percent of NRCA members' work involves reconstruction activities.

Accounting for the broader distinction of new construction vs. reconstruction work allows room for healthier discussion about how to best prevent falls. In its proposal to OSHA, NAHB appears to seek to codify the approach previously accomplished in the interim guidelines. NRCA agrees with NAHB's request.

State-plan states

OSHA state-plan states have the discretion to create their own safety rules as long as they "are at least as effective" as the federal ones. This has led to some interesting developments. Based on their own data and deliberations, Arizona, California, Kentucky, Michigan and Oregon have issued varying trigger heights, including 6 feet, 10 feet and even 20 feet, in their state regulations. The states may argue the term "as effective as" has historically been viewed in light of the effect of rules on worker injuries, not on specific wording or requirements of unique federal provisions.

For example, in California, there are nine fall-protection options from which to choose for steep-slope roofing work. Importantly, workers in California have had fewer roofing-related accidents and injuries than workers in states covered by federal OSHA. And California's rules have been in effect for more than 20 years. It also is important to note California's rules were developed through working with the public and affected industries to devise a fall-protection methodology that makes sense and helps prevent falls.

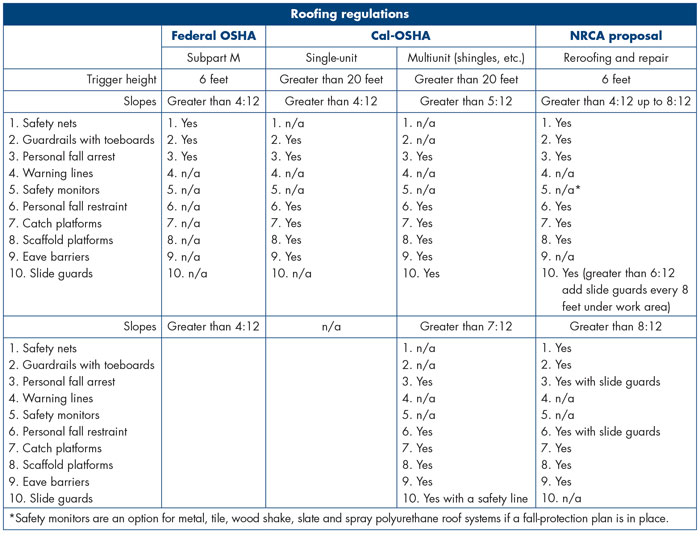

NRCA, in its discussions with OSHA since the interim guidelines' rescission, presented its suggestions for a regulatory approach that allows for a broader choice of fall-protection options. The figure shows NRCA's submittal. The key distinction in the roofing industry is not whether it's new construction or reroofing work (though those are important distinctions to be made) but rather the ground-to-eave height, slope and roof system being installed. California did a remarkable job of accommodating these factors. NRCA has provided its own guidelines for what options should be available to roofing contractors when they assess risks posed by roofing work.

Continuing dialogue

NRCA continues to seek to work with OSHA in hopes the agency will come to better understand how to protect the roofing industry's workers. The stark reality is most fatalities from falls off roofs result when no fall protection is used. Narrowing the fall-protection options available to contractors flies in the face of established risk management principles and does nothing to enhance worker safety; in fact, it only increases the chances for worker injuries and deaths. And that is the last thing anyone wants.

Thomas R. Shanahan, CAE, is NRCA's associate executive director of risk management.

In its 1994 regulatory preamble to Subpart M, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) stated: "Infeasible … means that it is impossible to perform the construction work while using a conventional fall protection system, or that it is technologically impossible to use a conventional system."

The agency noted economic infeasibility cannot be the basis for failing to provide conventional fall protection. OSHA stated a roofing contractor is required to establish specific circumstances that preclude reliance on conventional fall protection and, with regard to personal fall-arrest (PFA) systems, examples of those circumstances include "… inability to provide safe anchorage; danger of lifeline entanglement; likelihood that lifelines, especially self-retracting lifelines, will be mired in grout; likelihood that completion of work would be prevented by fall protection; and inability of [PFAs] to function due the configuration of the work area … ."

OSHA has not published a specific definition of the term "greater hazard." However, the agency stated in the preamble that a greater hazard defense to a citation is established "by demonstrating that the hazards created by compliance with a standard are greater than those created by noncompliance."

With regard to greater hazard, OSHA stated: "… [T]here may be cases where the installation or use of [PFA] systems poses a greater hazard than that to which employees performing the construction work would otherwise be exposed. The Agency will expect an employer who seeks to make that case to indicate specifically how compliance with the requirement for [PFAs] would pose a greater hazard. OSHA will assess each such case on its particular merits."

Other fall-protection methods may be used only if a contractor determines conventional fall-protection methods are infeasible or create a greater hazard for workers and the contractor develops a written fall-protection plan addressing the following requirements found in 29 CFR §1926.502(k):

- The plan must be prepared by a qualified person, be up-to-date and developed specifically for the site.

- Changes to the plan must be approved by a qualified person.

- A copy of the plan with all changes must be maintained at the job site.

- Implementation of the plan must be under the supervision of a competent person.

- The plan must document the reasons conventional fall protection is infeasible or creates a greater hazard.

- The plan must discuss other measures that will be taken to reduce or eliminate fall hazards to workers not protected by conventional fall-protection methods.

- Locations where conventional fall protection cannot be used must be identified and classified as controlled access zones; compliance with provisions of 29 CFR §1926.502(g) relating to controlled access zones is required.

- If no other fall-protection measure has been put in place, the employer must implement a safety-monitoring system as described in 29 CFR §1926.502(h).

- Employees designated to work in the controlled access zone established in the plan must be identified by name or other manner in the plan, and no other workers may enter the controlled access zone.

- The employer must investigate any serious falls or incidents at the site to determine whether the fall-protection plan must be revised to prevent future incidents.

Regarding the site-specific requirement, OSHA stated in an instruction issued in December 2010: "A written plan developed for repetitive use for a particular style/model home will be considered site-specific with respect to a particular site only if it fully addresses all issues related to fall protection at that site."

This differs from the strict requirement of the regulation that a written fall-protection plan be "developed specifically for the site" and authorizes repetitive-use plans that could, apparently, be based on similar characteristics of a job site, such as single-story; multistory; multilevel; low-slope; steep-slope; or tile, slate or cedar shake installations. A determination of infeasibility or greater hazard in the use of a conventional fall-protection method still would be required.

Did you know?

NRCA has all the information you need to ensure compliance with OSHA's fall-protection regulations, including free Roofing Industry Fall Protection From A to Z classes and a new comprehensive compliance program, Serving Up Safety: A Recipe for Avoiding Falls on the Job! For more information, visit shop.nrca.net.