Here’s an unpopular take: A SWOT analysis can be extremely helpful to a company or organization. I know sometimes a SWOT analysis gets a bad rap, and here’s why: It often means having to participate in a drawn-out session where a group is asked to air opinions about the company or organization and the environment it competes in, categorizing each as a strength, weakness, opportunity or threat, and then report their findings. The notes are recorded and distributed for consideration. Some new rules and/or policies may result, and everyone goes back to business as usual.

Many times, SWOT analyses net little more than a wish list, complaint repository, the latest accomplishments, or the current fears circulating the news and airwaves. Usually, not much changes, improves or happens after a SWOT analysis unless you count the morale crash of those whose work just got branded a “weakness” or the boost to those branded a “strength.” This lasts until the next SWOT analysis occurs, the tides turn and everyone hopes they never have to do one again.

But a SWOT analysis is not meant to net good (or bad) ideas, demoralize, empower, team build or scare people about the future. It is a strategic tool that can greatly assist an organization’s strategic plan. In addition (and importantly) it should be used to consistently identify and communicate strategies to meet current and future challenges with confidence and thoughtfulness.

The model

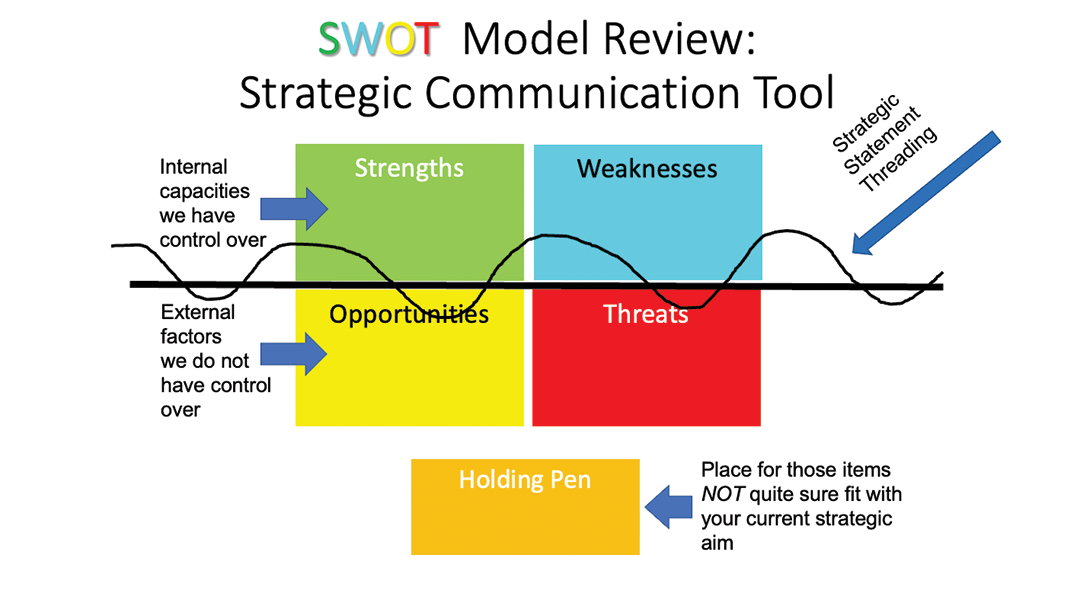

The model I use to teach SWOT analysis is in Figure 1. First, notice I refer to the analysis as a strategic communication tool. This perspective is important. It is meant to convey the SWOT analysis is a mechanism to sort and identify how an organization will express its responses to opportunities and/or threats posed by the market(s) it competes in.

Next, in the matrix, strengths and weaknesses are presented on top, and opportunities and threats are below. The top and bottom are used for completely different ends. This separation is key to understanding what responses go in which boxes.

As you perform a SWOT analysis, you (and others) will identify attributes about the organization and its market. There are two filtering processes used to ascertain where items will be placed in the matrix. Above and below the dark line are two statements with arrows: “internal capacities we have control over” and “external factors we do not have control over.”

Let’s say “adding metal roof system installations to our services” is the item being filtered. It is something the company has control over, so it will be placed above the line. Now that you know which side of the line you’re on, the second filter is used to ascertain whether it is a strength or weakness. Because this is a new venture, the statement likely is a weakness as there will be many things to do to ramp up this new line of business. But if you recently purchased a separate company that performs only metal roof system installations, you’d likely consider the item a strength.

Now, let’s say the Occupational Safety and Health Administration promulgates a new crane standard that significantly affects crane operator certifications. OSHA issuing the new standard is not something your company has any control over, so it resides below the line. Using the second filter, where will it reside? If you had no idea this was coming and you are being told by industry safety professionals the new rule is onerous, it likely is a threat.

Another example: A new tax incentive for homeowners who install or replace their roofs with metal roof systems within the next 12 months took effect. Is this an opportunity or a threat? For any residential roofing contractor who can install metal systems, it would be an opportunity. But if you do not install metal, you’d certainly consider this a threat.

During this analysis, there will be some discussion items that fall outside the business scheme but may have some reason not to be summarily dismissed. In the tax incentive example, if a roofing contractor does not install metal but might in the future, the metal roofing issue can be placed in the Holding Pen. But once the contractor decides metal roof system installation will not be a part of the company’s offerings, for example, the idea should be removed from the pen.

An unfortunate choice of words

The terms strengths and weaknesses are part of a memorable acronym, but they do little to help the process of creating strategic statements. Because each word can create an emotional response and, as such, thwart objective thinking, I prefer the terms competencies and challenges, which are neutral and allow participants to think more objectively about their company.

To me, it is almost insulting to have anything labeled a weakness. Why create extra baggage when you’re trying to achieve critical thinking? Strength is not much better. It is too strong a word to use given the dynamic nature of any company affected daily by external factors that can change a current success into a future failure. Once something is labeled a success, it likely gets less critical attention, which is not optimum for an organization that works best when it is nimble.

When conducting a SWOT analysis, take care to explain a strength should be considered a current organizational competency (something your company is doing well) and a weakness as an operational challenge you could be doing better or are working to improve. This can help reframe the discussion toward a more realistic organizational assessment.

Strategic statements

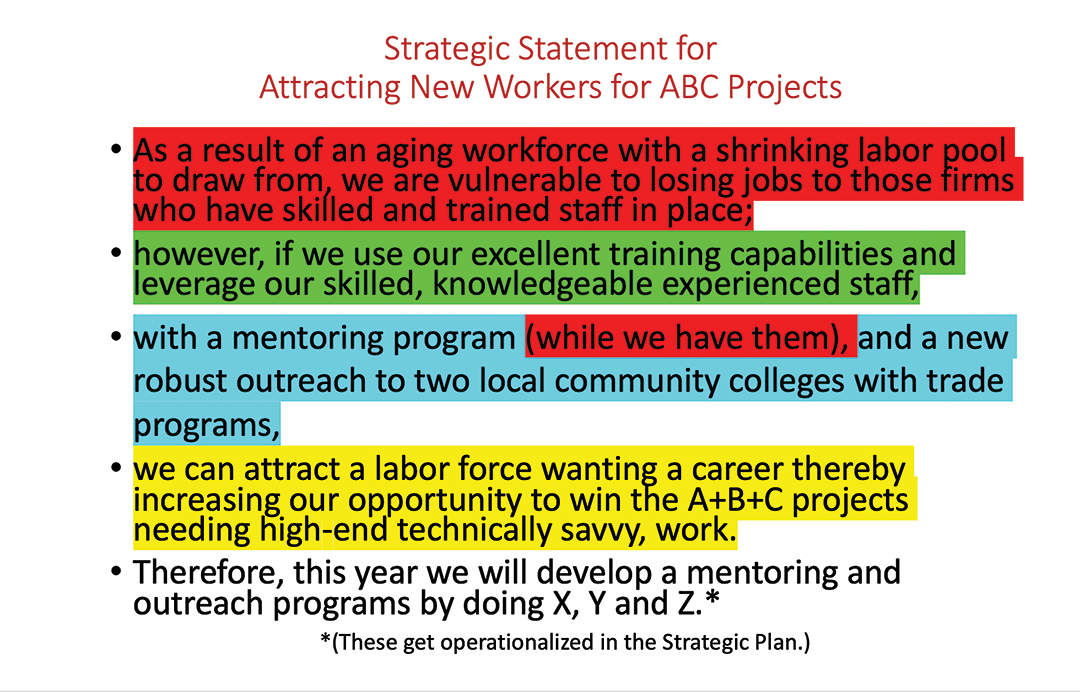

A strategic statement is the actionable end result of a SWOT analysis. Based on what your initial SWOT process reveals, you can identify topic(s) needing to be addressed (see Figure 2).

Notice the arrows in the figure. These indicate the strategic statement will be created tying the external factors to the internal capabilites. Consider what is occuring outside the company’s four walls that is presenting opportunities and/or threats and populate the Strength and Weakness boxes according to how well you are positioned (or not) to respond.

The strategic statement in Figure 3 is color-coded to align with the SWOT boxes to reach a concluding actionable statement. The strategic statement’s X, Y and Z goals become the basis for the strategic plan’s mission, long- and short-term objectives, and day-to-day tactics. The statement ties these boxes together and concludes with a game plan to be operationalized (technically as part of your strategic plan).

If you do not have a strategic plan, doing a SWOT analysis is a good place to start. What likely will become apparent are two important questions: Who are we, and who do we want to be? Without these filters, an organization risks being rudderless and possibly trying to be everything to everyone, which is usually not a successful strategy. Knowing your lane(s) and where you want to go is key to successful decision making and the company’s future.

An ongoing process

Once you have competency in performing a SWOT analysis, there are three intervals and perspectives I recommend doing consistently. First, at six- to 12-month intervals, do a 25,000-foot view analysis. In other words, imagine you can rise above your business and look down. This point of view is wide and, depending on the reach of your market(s), could be nationwide. Do your best to consider where your company will be in three or more years. Where do you see storms gathering, or are there blue skies? Is there anything the company should be taking advantage of or be concerned about? For example, are there news reports predicting high employment rates in 18 months, or is OSHA going to release a new standard in six months?

At three- to six-month intervals, do the same but now from a 10,000-foot view looking to see whether those previously identified storms or skies have materialized or a new opportunity or threat emerged?

These two exercises will help identify areas that need more attention. You can assign a team(s) to take on one or both of these efforts; however, to avoid groupthink, have each member do his or her own research, and bring the group together to discuss what they discovered.

Finally, from time to time, reach out to external stakeholders who know your company, such as your lawyer, banker, supplier(s), trusted customers, etc., and ask them to assess your strengths and weaknesses. These perspectives will provide information regarding how others view your internal operations. Also, ask what they are seeing, hearing and experiencing that may pose an opportunity or threat. Their points of view may be of great value.

Take it slowly

If you’ve never done a SWOT analysis or have and your experience was unpleasant, what I am proposing likely will seem daunting. Take it in small steps. Address one threat you feel comfortable weighing your strengths and weaknesses against and have your leadership team do the same exercise. Then, put all the information into a big SWOT chart, and look at creating smaller, targeted SWOT analyses as described and from each create a strategic statement. Once you have done that, you prioritize them and move toward implementation.

When an organization becomes focused, it finds efficiencies and uncovers fresh ideas. The organization finds its balance and sees its resiliency. As a strategic effort, a SWOT analysis helps any team member, department or organization communicate issues objectively by articulating how the issues are affecting (or may affect) the company and identifies a path forward. It can be a powerful strategic and communication tool.

TOM SHANAHAN, CAE, is a leadership coach and consultant and executive director of NRCA’s Future Executives Institute.