Used by roofing workers nearly every day, ladders are one of the most common pieces of equipment found on roofing job sites. Design, construction, setup and use of all types of ladders are established by the American National Standards Institute’s Accredited Standards Committee (A14), the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s rules in Subpart D of General Industry and Subpart X of Construction, and the EM 385 manual from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, among others.

Although numerous standards have been developed, the construction industry continues to suffer fatalities caused by improper ladder setup and use. According to the Department of Labor’s Bureau of Labor Statistics, during 2017 to 2018, 156 workers across all industries died in incidents involving ladders as the primary source of the fatalities. Of those 156 workers, 91 worked in the construction industry.

For roofing, OSHA’s rules under Subpart X, 29 CFR 1926.1050-1060 are applicable in most cases and OSHA enforcement reflects the seriousness of improper ladder use in the industry. OSHA’s federal offices have issued nearly 1,100 citations to roofing companies for workplace violations of ladder regulations, totaling $3 million in fines during 2018-19.

To protect workers from ladder falls, proper ladder setup and use must be implemented and adhered to every day.

Basics

OSHA requires a stairway or ladder at personnel points of access where there is a break in elevation of 19 inches or more and no ramp, runway, sloped embankment or personnel hoist is in place. This requirement often is ignored on roofs with multiple levels because workers find it easier to climb an engineered solution such as a ramp. However, ladders should be the only access method used.

When selecting a ladder, there are three common materials from which ladders are constructed: metal, fiberglass and wood. Each has pros and cons.

Metal ladders usually are made from aluminum, which is strong and lightweight but conducts electricity. As a result, metal ladders must be kept clear of electrical equipment and power lines. A better option to use when working around power lines is a fiberglass ladder.

Fiberglass ladders are nonconductive, allowing workers to use these ladders around electricity though distance requirements still should be maintained depending on the source and voltage rating of electricity in the vicinity of the ladder. Fiberglass ladders can be rated specifically for construction use and typically hold up to daily roofing work.

Although fiberglass ladders have a lot of upsides, fiberglass and wood ladders can be heavier than aluminum ladders, which can be an issue during setup if the ladder has a substantial length that demands more than one worker to raise or lower it. Wood ladders can cost less than fiberglass and metal ladders, but they also can conduct electricity particularly if the wood has absorbed moisture.

Every ladder must have a label identifying its duty rating—the maximum amount of weight the ladder is capable of supporting. Following are the established categories of duty ratings under ANSI’s A14 standards:

-

Type IAA (special duty): 375 pounds

Type IA (extra heavy duty): 300 pounds

Type I (heavy duty): 250 pounds

Type II (medium duty): 225 pounds

Type III (light duty): 200 pounds

For roofing, Types IAA and IA generally meet the demands of most job sites when the average weight of a worker and the tools he or she may carry are considered.

Inspection

The American Ladder Institute recommends a ladder be inspected when initially purchased and each time it is placed into service. Before using a ladder, make sure its rails and rungs are free of oil, grease, mud, adhesives, ice, snow and/or asphalt that could hinder a user’s grip or footing. Inspect the rung locks to ensure they move freely and engage the rung securely without binding. Check the integrity of the anti-slip feet or shoes by making sure they move freely, and make sure the rubber pad is in place as this is commonly damaged or missing.

Some ladder shoes have spurs that allow the feet to be pushed into soil for more stability. Check the spurs for bends that might make it harder to push the feet into soil. On all ladders, inspect the step or rung connection to the siderail for structural integrity. This is a critical area that also is difficult to repair if the step or rung is loose, corroded or otherwise deteriorated.

The American Ladder Institute states it is improper to attempt to repair a ladder with a defective siderail. When an inspection uncovers a ladder with a bent or broken siderail, the ladder should be cut up, discarded and removed from the job site so no one can attempt to use it in its defective condition. Also, if an extension ladder is equipped with a rope to raise and lower the fly section, check the condition of the rope, the pulley the rope feeds through and the connection to the fly section.

Setup

Before setting up a ladder, check the building perimeter for the safest area to set up:

- Look for level areas to place the ladder for greatest stability.

- Note the location of power lines, transformers, substations, solar arrays or other electric components and set up away from those components.

- Check for driveways, walkways, doors and/or gates that can increase the possibility the ladder could be struck and displaced.

- Be aware of exhaust fan shrouds, water discharge outlets and other components that may affect a worker on a ladder or make the ladder unstable.

- If interior access to the building is available, check the roof underside in the area where the ladder is expected to be set up to see whether there are any indications of rot or deterioration of the roof deck or skylights in close proximity to the ladder dismount area.

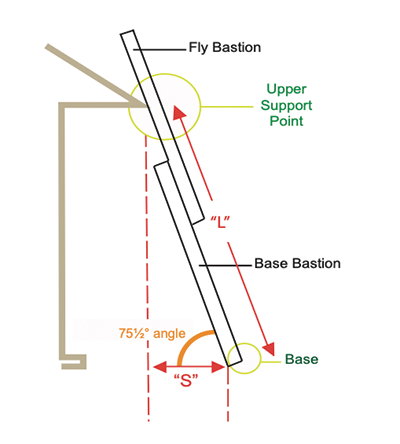

The Center for Construction Research and Training’s diagram for properly setting up an extension ladder

The Center for Construction Research and Training’s diagram for properly setting up an extension ladder

If a ladder is long and heavy, it may be necessary for two workers to set it up. This can be accomplished by a couple of different techniques that require the feet to be braced by a wall or having one worker brace the ladder’s feet while another worker walks the ladder up.

Under OSHA rules, an extension ladder should be set up at a 1:4 ratio, or what is more specifically described in other training resources as a 75-degree angle. The calculation results from moving the base of the ladder out from the building 1 foot for every 4 feet of ladder length (sometimes referred to as “run”) from the ground to its resting point on a building.

Photo 1: Once set in the proper place and raised, a ladder should extend 3 feet over the eave and be secured at the top by tying off to a point that can resist the ladder from sliding.

Photo 1: Once set in the proper place and raised, a ladder should extend 3 feet over the eave and be secured at the top by tying off to a point that can resist the ladder from sliding.

For example, if a ladder is resting on an eave and the ladder run (represented by “L” in the figure) is 16 feet, the base of the ladder should be placed 4 feet away from the building. This is more complicated when the building has an overhang that must be accounted for as in the figure (represented by “S”). Note the imaginary line from the roof resting point to the ground.

Once set in the proper place and raised, a ladder should extend 3 feet over the eave and be secured at the top by tying off to a point that can resist the ladder from sliding (see Photo 1). Manufacturers recently have marketed clamps and various fastener brackets that make this step easier than in the past. In some instances where the bottom of the ladder can be displaced, it may be necessary to secure the base of the ladder (see Photo 2).

Photo 2: In some instances where the bottom of a ladder can be displaced, it may be necessary to secure the base of the ladder.

Photo 2: In some instances where the bottom of a ladder can be displaced, it may be necessary to secure the base of the ladder.

Throughout a project, weather-related issues such as wind, snow, ice and rain can create unique safety challenges. For example, the stability of a ladder must be considered when high winds or ice are present, and points of access or egress are challenged by accumulating snow or rain that can present slippery conditions on and around the ladder. Snow, mud and ice can stick to boots and be transferred to ladder rungs, creating issues while trying to climb. Before a worker ascends or descends a ladder, the ladder and areas around it must be inspected to ensure safe setup and use.

Use

There are several rules and instructions for climbing or descending a ladder, including those from OSHA and manufacturers as well as other standards intended to minimize injuries, but sometimes they are confusing in application.

OSHA states: “An employee shall not carry any object or load that could cause the employee to lose balance and fall.” A discerning reading of this requirement could leave a safety trainer puzzled: What does it mean that something “could” cause an employee to fall? How is the foreseeability of that determined to put an actual protocol in place for a roofing company?

Ladder manufacturers and others also may contribute to the confusion by referencing the calculation for the duty rating of a ladder being proper if a worker’s weight, tools and materials weigh less than the duty rating of a ladder. The unspoken premise being that carrying 80 pounds of shingles up to a roof may be OK if the total weight placed on the ladder is below its duty rating.

Some manufacturers temper that interpretation by requiring “three points of contact” when climbing or descending a ladder—one hand and two feet or two hands and one foot in contact with the ladder at all times. Following a three-points-of-contact approach would seem to indicate a worker could not carry anything up a ladder because it would be impossible to maintain three points if a worker were holding something in one hand. OSHA, however, also says a worker must always use at least one hand to grasp the ladder when going up or down—language that seems to support the premise that a worker can carry things if his or her balance will not be affected (see “OSHA’s three points of contact” below).

Photo 3: Walk-through ladder accessories can help workers maintain balance when getting on and off a ladder.

Photo 3: Walk-through ladder accessories can help workers maintain balance when getting on and off a ladder.

The concept of three points of contact also is limiting if a worker uses the rungs to climb a ladder instead of sliding his or her hands along the siderails. Some workers believe the rungs are safer to use because an overhand grip is stronger and they cannot grip the siderails with sufficient strength to avoid falling if a foot slipped.

The counter argument is twofold: Workers do not grip the rungs because the rungs often are full of gunk such as asphalt, adhesive or mud, so holding clean siderails means a worker maintains balance. The practical issue with three points of contact while using the rungs is a worker cannot move a hand unless both feet are set and cannot move a foot unless both hands are set. This significantly increases the time involved on even a short ladder climb.

In 2010, the Center for Construction Research and Training studied ladder falls and reported loss of grip was the cause of ladder falls in 1% of cases studied while loss of balance was a cited cause in 18% of cases. Therefore, the issue may be how best to maintain balance when going up or down a ladder and not one of grasping a rung or siderail.

Another common action preceding a ladder fall happens when a worker has to move his or her body around the ladder to get on or off it. Often, this is when a ladder slides or moves enough to make the worker lose balance. A solution may be walk-through ladder accessories, such as the one pictured in Photo 3, similar to rooftop features on fixed ladders.

Don’t miss a step

The frequency of ladder injuries and fatalities indicates employers must better prepare their workers to properly set up and use ladders. Arriving at a studied consensus for how best to train workers in several aspects of ladder use would be a significant step toward maintaining worker safety. In addition, repetition of undisputed, basic ladder safety setup training from recognized industry sources, such as the Center for Construction Research and Training and the American Ladder Institute, is necessary to help ensure ladder safety principles delivered during training are put into place on job sites.

Harry Dietz, J.D., is an NRCA director of enterprise risk management, and Tom Shanahan, MBA, CAE, is NRCA's vice president of enterprise risk management and executive education.

OSHA’s three points of contact

In June, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration issued a letter of interpretation in response to a request regarding whether a worker must grasp the rungs of a ladder when going up or down. OSHA’s response states: “The intent of 1910.23(b)(12) is for employers to ensure that workers maintain ‘three-point contact’ (i.e., three points of control) with the ladder at all times while climbing.”

However, three points of contact as described in OSHA’s letter of interpretation may not withstand practical scrutiny. When true three-point contact is maintained—using only the rungs for a handhold—climbing is slowed by the deliberate sequencing of a foot being moved only after both hands are securely holding a rung and vice versa. Try it to see how long it takes to climb a ladder.

But when climbing a ladder using the siderails, the hands never lose contact with the ladder thereby making the three-point-contact protocol easy to maintain while possibly addressing the loss-of-balance issue.

OSHA adds further confusion by stating in the letter of interpretation that the regulation “would not preclude an employee from carrying such items while climbing a ladder so long as the items don’t impede the employee’s ability to maintain full control while climbing or descending the ladder.” This contradicts a common training admonition to never carry anything up a ladder using hands and the three-points-of-contact idea.

NRCA and its Health and Safety Committee grapple with the terms to use during training to prevent ladder-related accidents. “Three-point contact” means having three points of contact with a ladder, which OSHA clarified in its letter of interpretation to mean a deliberate climb up a ladder. But OSHA’s statements to “ ... use at least one hand to grasp the ladder ... ” and “ ... not carry any object or load that could cause the employee to lose balance or fall” seem contradictory.

NRCA is concerned about the current imprecise understanding and use of three points versus two points of contact terminology as it relates to effective training and ladder use. Three points of contact can be achieved either through a deliberate climb or use of siderails. Two points of contact occurs during a typical safe climb up a ladder where the opposite hand and foot ascend or descend in unison. This cross-body climb balances body weight and allows smoothness of movement.

Using the correct terminology and understanding the best climbing approach demands further research and analysis into causation of falls. In particular, the effects of allowing objects to be carried also must be analyzed so ladder-training protocols truly can help assure worker safety.

App helps determine ladder angle

An easy way to determine ladder angle is to use the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health’s ladder app, which allows a worker’s smartphone to gauge the proper ladder angle. The app is available at www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/falls/mobileapp.html.