For decades, the construction industry has invested heavily in safety. It has never had more rules, more technology or more safety professionals than it has now. Companies have expanded safety departments, adopted new technologies, dedicated shelves to procedures and developed increasingly detailed planning tools. Yet despite these efforts, the industry continues to suffer a stubbornly high rate of serious injuries and fatalities. The paradox has become impossible to ignore: More safety controls do not necessarily mean safer work.

Rethinking safety

This paradox has prompted a re-examination of assumptions. If more rules, paperwork and observation checklists haven’t solved the problem, what will? A growing body of scholarship and field experience points to two answers:

- Focusing intently on the limited set of hazards capable of producing serious injuries and fatalities rather than treating all hazards as equal

- Reducing administrative clutter that diverts attention away from identifying and controlling high-risk exposures

Matthew Hallowell, professor at the University of Colorado-Boulder and founder and executive director of Construction Safety Research Alliance, conducted research in energy-based safety and serious injury and fatality prevention (or SIF prevention as it is more broadly referred to in the safety profession).

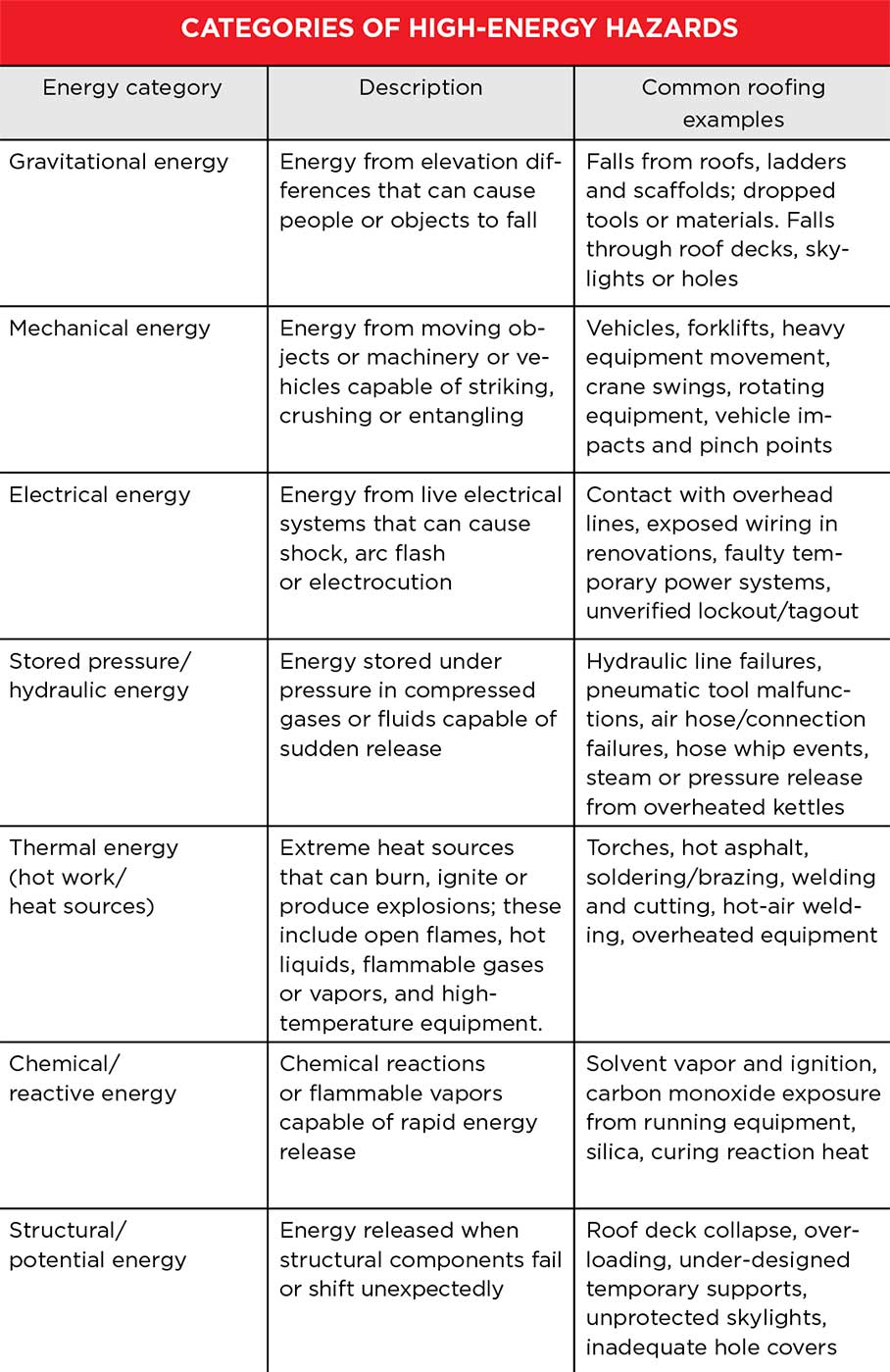

Hallowell’s energy-based safety research has fundamentally changed how safety professionals understand risk. His main idea is simple: Injury severity depends on the amount and type of energy a person encounters. The more energy involved, the higher the chance of serious harm. If organizations design their safety programs to identify, control and verify high-energy interactions, serious injury and fatality prevention can be achieved more effectively and systematically.

The figure below includes the most common categories of high-energy hazards discussed in Hallowell’s book Energy-Based Safety: A Scientific Approach to Preventing Serious Injuries and Fatalities (SIFs).

When organizations focus their resources on controlling energy, serious injury and fatality prevention improves. Conversely, when they spread focus across an increasing number of administrative tasks and low-value requirements, attention diminishes, and the most serious risks go unnoticed.

Safety clutter

Hallowell’s work suggests safety systems should focus less on generating volume and more on sharpening attention to the high-energy exposures that reliably drive serious injuries and fatalities. Many companies have developed systems that treat every hazard equally. This approach leads to scattered attention that masks the conditions that truly matter. Field leaders can become overwhelmed with paperwork and procedural demands that seem disconnected from their daily realities. Workers might come to see compliance with documentation as more important than maintaining effective physical controls. Supervisors, stretched across numerous minor tasks, may lack the capacity to identify the one missing control that could prevent a major incident.

This accumulation of low-value requirements often is described as “safety clutter,” made up of safety rules, documents, procedures and activities that consume time and attention without contributing to improving the safety of the work in a meaningful way.

Safety clutter does not arise from negligence or apathy; it happens because organizations respond to incidents with the best intentions by layering on new requirements rather than examining whether the existing system has become too complex. Meanwhile, little if any existing safety burdens are removed.

Over time, companies have inadvertently created safety systems that are difficult to navigate. What was once considered a safety solution may have evolved over time into safety clutter.

Safety clutter, which is unique to each organization, can communicate the unintended message that administrative compliance is more important than operational reality. Workers quickly learn producing paperwork is rewarded more predictably than stopping work for unsafe conditions or reporting near misses.

Even worse, clutter can crowd out authentic safety conversations. Instead of discussing warning signals or faulty controls, supervisors may be pressured to complete checklists or verify compliance metrics that have little bearing on serious injury and fatality prevention.

Decluttering safety

To change the trajectory, safety clutter needs to be eliminated. Decluttering safety does not mean lowering standards, relaxing expectations or removing protections. On the contrary, decluttering is a strategy for raising the standard of safety performance by stripping away distractions so high-energy hazards can receive the disciplined attention they deserve.

For example, a company may previously have required a multipage job hazard analysis, a separate fall-protection plan, a ladder checklist and a scaffold inspection form before allowing elevated work to begin. Even when completed diligently, these documents can obscure the few conditions that truly determine whether work is safe, such as the quality and placement of anchor points, the integrity of guardrails, the configuration of fall-arrest systems or the stability of the work surface.

When these critical elements are distilled into a more focused conversation at the point of work, supported by a simple verification step rather than a stack of forms, field leaders can more easily see whether high-energy exposures are adequately controlled. Workers can then spend more time discussing the actual task and less time navigating paperwork. This level of clarity can improve situational awareness, build trust and encourage engagement, something a checklist cannot do.

Successful decluttering efforts generally begin by carefully reviewing existing safety systems to identify which tools and requirements genuinely contribute to risk reduction. Items that exist solely to support regulatory burden or administrative, insurance or traditional expectations are evaluated honestly against their practical ability to control energy. Many organizations discover a significant portion of their existing safety documentation can be consolidated, simplified or eliminated entirely without compromising safety. In fact, removing these burdens often allows supervisors and workers to devote more attention to genuine risk reduction.

Once clutter is removed, companies can reorganize their safety efforts around an energy-based framework. This involves educating leaders, supervisors and workers to think in terms of the physical forces present in their work and to recognize when those forces reach levels associated with serious injury or fatality potential.

Instead of starting every pre-task discussion by listing generic hazards, teams begin by identifying the types and magnitudes of energy involved in the tasks they will perform that day. Roofing work at heights involves gravitational energy that can be lethal even from modest elevations. A crane lift involves suspended loads and dynamic mechanical energy. A roof tear-off may involve hidden structural energy that had not been fully identified and controlled.

Focus on what matters

When shifting focus to energy hazards, the next step is to define the essential controls that, if in place and verified, can reliably prevent serious harm. These are not lengthy lists of every possible precaution; they are a handful of measures that are indispensable for high-energy work.

After identifying critical tasks involving high-energy hazards, roofing company owners or safety directors should create a critical task inventory and pinpoint specific controls. When organizations identify these controls and embed them into daily routines, they create a compact but highly effective injury-prevention system.

Traditional hazard identification lists hazards as separate items, such as fall hazards, electrical hazards and pinch points. Energy-based models shift the focus from categorizing hazards to measuring exposure and understanding the dynamic interactions between workers and energy.

This approach elevates safety practice by asking:

- What energy is present?

- What is the magnitude of that energy?

- How close are workers to the energy?

- What barriers exist?

- How reliable are those barriers under real working conditions?

- What could cause a rapid change in exposure (environmental shifts, production pressure, fatigue, unexpected conditions)?

Learning from work

Leadership is central to fostering a learning mindset by simplifying systems, clarifying expectations and reducing administrative burdens, which can enable supervisors to prioritize critical controls over paperwork. By promoting cross-functional collaboration and integrating learning into daily processes, leaders cultivate a culture of continuous improvement and adaptation.

Examples of high-energy hazards

Falls from heights remain the leading cause of workplace-related death in the roofing industry, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, driven by missing or poorly designed fall-protection systems, inadequate anchorage or inconsistent tie-off practices.

Heavy equipment contributes to a high volume of struck-by and caught-between events, particularly when workers are exposed to blind spots, uncontrolled movement or inadequate traffic separation.

Electrical energy, often invisible and misunderstood, continues to cause fatalities during equipment operation, overhead work or utility installation.

Structural instability, leading to failure or collapse, can release enormous gravitational and kinetic forces.

Pressurized systems, from hydraulic lines to air receivers, pose immediate and violent hazards when they fail unexpectedly.

Decluttered, energy-based safety recognizes human error is normal, variability is inevitable and perfect compliance is unrealistic.

So the goal shifts from enforcing rules to a learning-based approach that emphasizes:

- Near-miss and early learning to identify high-energy hazards and opportunities for serious injury and fatality prevention and culture improvement

- Operational dialogue between workers, supervisors and engineers

- Post-task reviews that can include near-miss reporting and analyzing incident reports to identify potential risks before they escalate to serious incidents

- Nonpunitive reporting mechanisms

- Continuous improvement of engineered controls

When organizations learn from everyday work not just incidents, they uncover patterns and conditions that would otherwise remain invisible until a catastrophic event occurs.

Technology

Technology also has a role to play provided it supports rather than complicates the system. Digital tools that replace manual forms, simplify pre-task discussions, automate verification steps and make high-energy exposures visible in real time can be powerful enablers. But technology must be chosen with restraint. Too often, digital platforms merely digitize clutter rather than eliminate it. The goal is a system that reduces friction, simplifies decision-making and aligns seamlessly with how construction work is performed.

Construction technology has advanced rapidly, but without disciplined integration, it can unintentionally add clutter. To support serious injury and fatality prevention, technology should:

- Reduce manual inputs

- Provide real-time visibility into high-energy exposures

- Simplify field workflows

- Automate verification where possible

- Support data-driven learning

Examples include:

- Wearable proximity sensors to alert workers when they are too close to machinery or equipment

- Digital dashboards to monitor safety compliance, track incidents and identify trends

- Automated lockout verification systems

- Drone imagery for elevated inspections

- Simple mobile tools for pre-task dialogues

Benefits of a lean approach

Construction companies that adopt uncluttered safety principles typically report measurable reductions in serious injury events, increased supervisor confidence and capability, stronger worker engagement, improved alignment between safety and operations, and reduced administrative burden.

Traditional, paperwork-heavy safety approaches have achieved all they are likely to achieve. They have been effective for reducing minor injuries, but they were never designed to address the physics-driven realities of today’s complex project environments. To finally move the needle on serious injuries and fatalities, the industry needs a new model—one that is simpler, clearer and anchored in the physical truths of work.

CHERYL AMBROSE, CHST, OHST

Vice president of enterprise risk management

NRCA