"He was a great installer, so I promoted him to foreman."— Contractor

"I liked it better when I was an installer."— Foreman

Why is it that someone sees leadership potential but the new leader wishes for the days of being a follower?

The classic reason roofing workers get promoted to the foremen level is because they do great work and get things done, leading their employers to assume they also should be able to train and lead others to do the same. However, as most newly minted foremen will tell you, they had no idea how difficult it is to get other people to do what they do. For some, the frustration isn't worth the extra money; others learn to live with the daily grind. Most have a sincere desire to understand what it takes to succeed in a leadership position but don't know how to move forward.

During the past 18 years, I've taught NRCA's For Foremen Only, Level 1, class to thousands of foremen. What class participants reveal is having the title "foreman" isn't enough, and to be successful, they need to learn what it means to lead, manage and communicate effectively.

Learning to lead

When teaching the class, the first thing I do is describe the difference between knowing which situations call for management tools and which call for leadership skills. If the matter at hand is one where the result easily can be measured, such as quality, foremen need to use management tools to address it. Some other examples of issues that can be measured and determined as having met a goal include timeliness, customer satisfaction, productivity and housekeeping. If a goal is not met, a foreman can employ management strategies to improve results, which could mean devising and implementing new checklists, task descriptions, sequencing models, training programs, flow charts, etc.

However, if an issue involves a situation where a worker doesn't seem to care about the matter at hand, a foreman needs leadership skills to address it. Leading effectively inspires others to act in a way that is desirable for attaining job outcomes.

For example, a foreman can provide his or her crew with all the necessary fall-arrest equipment and training to properly use it, which are all management-related skills. However, if a worker is not inspired and/or empowered to care enough about his or her safety or that of co-workers, the foreman needs to use leadership skill to improve the situation.

Typically, after learning this distinction, foremen can see why, for example, instituting a management checklist usually doesn't change a worker's attitude. If anything, it can make the foreman's job more cumbersome because on top of it all, there's another task to do—fill out a checklist.

What can help is determining communication preferences of crew members. Foremen can conduct assessments to discover how people interpret verbal and nonverbal cues.

For example, some cues come in the form of voice volume, pitch and rate of speaking; body movements, including gestures, facial expressions and eye contact; and appearance, which includes clothing and posture. If a foreman's go-to style is to yell orders, he or she will observe some workers responding appropriately, some resenting it, some shutting down and others yelling back. The bottom line is at best the foreman can only get some workers to comply.

Understanding how a foreman gives direction or feedback matters as much as the words used—this is a key to leadership.

As eye-opening and interesting as communication styles and effective listening are, the reality of what it means—foremen spending time getting to know crew members—can generate anxiety because it can feel like more work. Appreciating the difference between managing and leading can help here. A manager sees one more task, and a leader sees the opportunity to connect. The ability to reach employees through relationships can yield greater commitment to job ownership, thereby reducing the task list.

But not everyone is a leader. Those who cannot establish rapport—even a little—may need to move to a more appropriate role or out of the organization. Of course, in the current labor shortage environment, letting people go is not optimal. This is where leadership training can help.

Getting training

The Center for Construction Research and Training’s Foundations for Safety Leadership program teaches foremen five critical safety leadership skills.

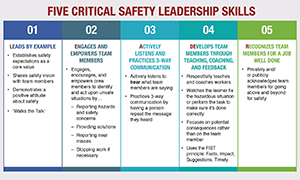

Although NRCA's For Foremen Only is a great option, there are additional resources contractors can use to expose foremen to some leadership skills. One option is a new safety leadership training course the Center for Construction Research and Training (CPWR) developed, with funding from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), called Foundations for Safety Leadership (FSL). It is a 2 1/2-hour training module designed to teach foremen and lead workers five critical safety leadership skills and how to put them into practice. (Although presented with the intent to foster and improve safety on the job, the program is universally applicable to anyone needing leadership skills training.)

Two key drivers led CPWR to recognize the need for such training. The first was discovered during a 2013 CPWR-NIOSH workshop where 70 construction stakeholders, including NRCA, worked together and agreed on eight key leading indicators of a strong job-site safety climate, one being site supervisor safety leadership.

The second came from a 2012 McGraw Hill-CPWR survey that showed many construction companies, regardless of size, require new foremen to take the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) 30-hour course to learn leadership skills. However, the OSHA 30-hour course didn't have a leadership training module until FSL became an official elective Jan. 1, 2017. It is well worth ensuring this module is taught to anyone who attends an OSHA 30-hour course. And it is well-suited to stand alone if a contractor sees the need to build leadership awareness and skills.

FSL is the result of a rigorous 18-month development process. Beginning in September 2014, researchers from CPWR and two Colorado universities worked closely with a 17-member curriculum development team that included OSHA 10- and 30-hour outreach trainers, construction workers, safety and health professionals from small and large companies, representatives of building trade unions, consultants and OSHA staff to make sure the final leadership module would meet the needs of foremen as well as those who would conduct the training. The final module contains foundational material plus 10 real-world animated scenarios designed to teach five critical safety leadership skills described in the figure.

More than 10,000 foremen throughout the U.S. have received FSL training. For roofing contractors who want to continue building their foremen's leadership competencies, there are additional programs they can implement. For example, NRCA's For Foremen Only, Level 1 and Level 2 programs, each one day long, delve into leading, managing and communicating. Thousands of foremen already have received the training.

In addition, this month, NRCA will launch its ProCertification™ offering for foremen. Foremen wanting to become certified by NRCA will have various training programs available to help them achieve the necessary level of competency for the certification exam. Those who pass the written exam will achieve certification.

A foreman's role requires management and leadership skills and an understanding of which ones should be used. Doing this effectively can be challenging, but those who can listen, communicate their needs and build rapport will positively affect their teams and enhance their job satisfaction.

Linda M. Goldenhar, Ph.D., director of research and evaluation at CPWR—The Center for Construction Research and Evaluation, and Tom Shanahan, MBA, CAE, is NRCA's vice president of enterprise risk management and executive education.

COMMENTS

Be the first to comment. Please log in to leave a comment.